A Living Nexus of Global Sustainability

By: Angel Kwok

January 17, 2019

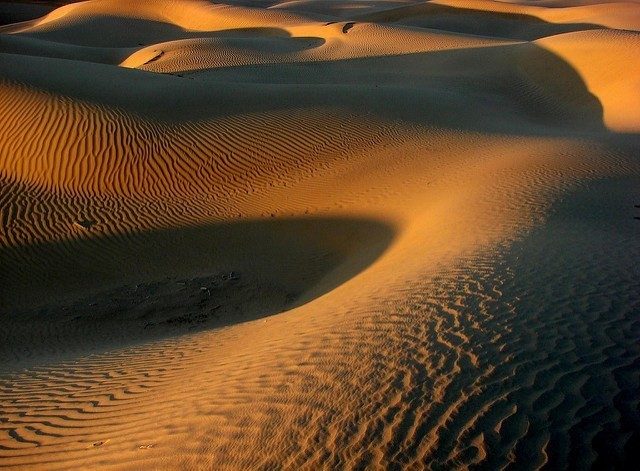

Dust coated my hair, lined my throat, and stung my eyes while an open Jeep transported me deeper into the Thar Desert. The one-way sandy trail was unforgiving; dunes bounced me around while the sun beat a steady cadence across my back, and I contemplated how people managed to live in such a desolate place.

Situated in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan, the Thar Desert borders south Pakistan and is the most humanly populated desert in the world where water security threatens its inhabitants. In partnership with Jal Bhagirathi Foundation (JBF), students from Virginia Tech’s Executive Master’s in Natural Resources (XMNR) program, myself included, ventured into the heart of Rajasthan to study its water management practices. With the looming threat of global climate change, the main suspect in the region’s series of droughts, adaptation is key to sustaining human life in the most remote of places.

After a three-hour commute from the city of Jodhpur, my classmates and I disembarked onto the dusty shoals of a village known as Navatala, comprised of approximately 50-60 people, the community welcomed us with a local traditional blessing before we sat cross-legged on a large sheet laid under the shade of a tree. As a Hindu community, most men sported turbans while women donned hijabs, leaving the faces of the children peering curiously from behind their respective guardians. Their homes were comprised of straw and mud huts, each hut serving a single function including a bedroom, kitchen, or food/crop storage room. In addition to the cluster of straw huts, underground water tanks, known as ‘taankas’ in local terminology, were actively under construction as means to harvest rainwater from the region’s monsoon season, June through September, the area’s key source of water.

The Jal Bhagirathi Foundation serves various roles to help establish water security throughout the region. The primary duty being financial assistance and supplementing up to 70% of the total cost toward individual household taanka projects. Such taankas are constructed with cement a costly ingredient, considering other more readily-available building materials, i.e., straw, mud, and even dried cow dung, and span a 10 to 20-foot diameter “catch basin” to collect and store rainwater. According to JBF, this essentially extends water availability from a previous four-month average to 10-12 months.

Additionally, JBF employs what can be considered project liaisons who make daily visits to villages not only to monitor taanka progress but also to build trust and rapport, as these communities exist in isolation and visitors are uncommon. Before the introduction of household taankas, water was typically trucked into the region. However, the water wasn’t free, which forced these remote communities to pool together funds for the purchase. Therefore, household taankas facilitated by JBF offset or completely eliminate the need to buy water.

My classmates and I were fortunate enough to observe several taankas during different stages of build, and I was awed by their rudimentary means of construction. No contractors were hired, no machinery was employed, but they were forged by the homeowners themselves. A farmer stood 10 feet deep in his would-be taanka pit, digging with a large hoe in bare hands and feet while his wife and daughter heaved out the dirt via rope and repurposed rice bag akin to a bucket of water in a well. A tree branch embedded in a flat rock and secured with a strip of camel leather served as a dirt tamper.

This image really provided perspective for me, demonstrating the holistic concepts discussed in the classroom being implemented in the real world, and it all came back to the basics. This was food, water, and energy in its rawest state. In this single snapshot, I was witnessing the intersect of three global issues we had studied: climate change, water security, and poverty. Realization set. The solution to one encompassed the remaining two. For instance, you cannot solve poverty without addressing water security and climate change and vice versa. These complex or tricky issues are multifaceted, and there is no silver bullet, but require a combined effort and inputs from various sources. Here, the inputs were JBF, individual homeowners, and communities who worked together to draft a solution.

Switching to a wider lens, while taankas provided an immediate solution against the forefront of drought, funds freed from purchasing water could go towards other basic needs such as electricity. As I walked past neat stacks of dried cow dung, commonly used to burn fuel, I also noticed electrical infrastructure in its initial stages of development. Tall, sandstone slabs were established similar to telephone or electricity poles, ready to provide the area with power. Ideally, the introduction of electricity would reduce the need for direct burns and therefore, eliminate carbon dioxide released directly into the atmosphere.

While I stared at the nexus of poverty, water shortage, and climate change, I left the villages of Rajasthan hopeful. Not only was interaction with the community invaluable as they proudly offered my colleagues and me tea, utilizing freshly pumped water from their taankas, but I was witnessing progress in the making. Such individual and small-scale efforts ultimately serve as a departure from the viciousness of water scarcity, poverty, and climate change.

---

Executive MNR program alumna Angel Kwok is an active-duty Lieutenant in the U.S. Coast Guard working in the Office of Port and Facility Compliance at Coast Guard Headquarters, Washington D.C. She is an outdoor enthusiast and occasionally dabbles in short-fiction writing and journalism.

The Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability thanks XMNR students Allie Dore and Angel Kwok for the use of their photos, and photographers who share their work through the Creative Commons License: Sankara Subramanian, Allie Dore, Angel Kwok, and Allie Dore.