Fairfax County Water Management – Part II

February 25, 2019

[In Part I of his three-part series, Environmental and Water Resources Engineering (EWR) graduate student Joe Riley-Ryan introduced the need for careful sustainability planning using Fairfax County, Virginia as an example. This week, Riley-Ryan dives deeper into issues such as watershed protection, grey water reuse, and protecting aquatic ecology.]

Public water supply source protection and demand reduction have been implemented in a variety of ways in Fairfax County, Virginia. One of the two main drinking-water sources for the County is the Occoquan Reservoir. Fairfax Water owns and operates this drinking-water supply reservoir and has easement rights on all of the properties surrounding the reservoir, which restricts building in those areas. This measure protects the quality of the water and will allow Fairfax Water the flexibility to increase the elevation of the reservoir pool, if necessary to meet future demands7.

Watershed Protection

There were two other major undertakings, which have resulted in the protection of this essential drinking water source for the County. The Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA) is a state of the art wastewater treatment facility, which first opened in 1978 to replace 11 inadequate treatment facilities. UOSA currently operates at a level resulting in wastewater effluent that meets the EPA’s standards for potable drinking water.

Another significant and controversial undertaking was the 1982 downzoning of about 41,000 acres of the County within the Occoquan Reservoir watershed. As a result, property owners are not allowed to develop residential properties to densities any greater than one single family home per five acres lot within a significant portion of the Occoquan Reservoir’s watershed8. While this may seem to be conflicting with the high-density approach to sustainable urbanization, maintaining low-density development and large percentages of open space in source watersheds promotes a safe drinking-water supply and reduces the energy inputs and costs of treating water to standards for drinking.

Grey Water Reuse

Fairfax County also implemented a successful project centered on reuse of wastewater effluent from the Noman M Cole Jr. Wastewater Treatment Facility, which is owned and operated by the County’s Wastewater Management Division, for non-potable uses.The project included the construction of five miles of pipes and pumps with a project cost of $15 million as well as $7 million in EPA grant funding. This allowed for treated wastewater to be sold at a price lower than that of Fairfax Water’s potable water.

Currently, the water is being sold to a solid-waste-to-energy plant operated by the private company, Covanta, for cooling purposes, and to the Fairfax County Park Authority for irrigation use at the Laurel Hill Golf Club and several south county ball fields. The program results in reducing demand for potable water sources by 500 million gallons a year and generation of $1 million per year in revenue from the sale of the reclaimed water9,10. The County is looking for more buyers for the recycled wastewater to expand the benefits of this program.

Protecting Aquatic Ecology

Federal, regional, and state regulations and initiatives have had a significant influence on the approaches taken to water management in Fairfax County. One very influential piece of regulation was the EPA’s 2010 establishment of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) of nitrogen, phosphorous, and sediment, which pollute the Chesapeake Bay11. Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), in turn, has adopted policies for reducing the state’s contribution of these pollutants to the Bay. These policies have affected Fairfax County by being rolled into their Municipal Separate Storm Sewer (MS4) Permit from DEQ, which requires them to manage non-point sources of a variety of pollutants that reach waterways through storm-sewer systems12.

Implementing projects and tracking progress toward compliance with the MS4 permit falls under the responsibility of the County’s Stormwater Management Program. Compliance with the permit requires extensive investment in monitoring conditions in streams, educating the public, planning and implementing water quality-control practices, inspecting and maintaining stormwater facilities, and enforcing penalties on those violating pollution prevention laws. The County’s Board of Supervisors has recognized the importance of these programs and approved a separate stormwater service district, a property tax, which funds the requirements of the permit13.

The County has implemented an array of capital project types aiming to improve water quality and ecology in local streams and regional waterways. Green infrastructure projects are one approach with the aim of restoring hydrology closer to that of a natural watershed in developed areas by installing rain gardens, infiltration facilities, and pervious pavement, among other practices. The Stormwater Planning Division looks for ways to implement green infrastructure facilities through stand-alone capital projects or by partnering with other County agencies on building projects in parks, schools, and other County facilities.

The County maintains a number of fairly large lakes or reservoirs built for regional stormwater management purposes. The sediment and nutrient capturing capacity of the lakes can be considerably enhanced through dredging and restoration projects. Another project type used to improve water quality consists of retrofitting older stormwater detention and retention ponds that were designed to reduce the “peak flow” of runoff during heavy storms with constructed wetlands for habitat creation and improved nutrient processing and pollutant removal.

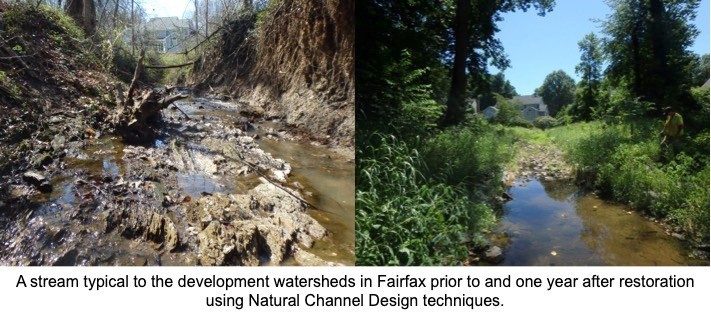

Since a large percentage of the County’s contribution of sediment, nitrogen, and phosphorous to the Chesapeake Bay is estimated to come from the severely eroding stream banks in the area due to development in their contributing watersheds, stream restoration using methods known as Natural Channel Design has been receiving a majority of the County’s new stormwater project funding. Stream restoration has been determined to be the most cost-effective way for the County to meet its TMDL requirements, so that is where most of their efforts are currently focused.

[In the final installment of this series, available on March 4th, Riley-Ryan will discuss the impact of land development and new construction, managing water and roadways, and outreach and education efforts.]

---

Joe Riley-Ryan is a graduate student in Virginia Tech’s Environmental and Water Resources Engineering (EW) Masters Degree program. He has also worked for Fairfax County’s Stormwater Planning Division for the past five years.

The Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability thanks the following photographers for sharing their work through the Creative Commons License: Jeffrey, Pvt Pondscum, Joe Riley-Ryan, and Roger W.

References

- Wu, (2014). Urban ecology and sustainability: The state-of-the-science and future directions. Elsevier, 125, 12.

- BioTchGuru. (2014). Urban Water Cycle. YouTube.

- Singh, V., et al. 2014. Water, environment, energy, and population growth: implications for water sustainability under climate change. Journal of Hydrological Engineering 19:667-673.

- United Cities and Local Governments. 2015. The Sustainable Development Goals: What Local Governments Need to Know

- Richter, B., et al. 2018. Assessing the Sustainability of Urban Water Supply Systems. AWWA Journal 110(2):40-47.

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). General Overview.

- Fairfax Water. (2018). Occoquan Reservoir. FairfaxWater.org.

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). Department of Planning and Zoning.

- US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Region 3, Water Protection Division. (2015). Water reuse project in VA providing multiple benefits.

- Chapin, J. (2013). Design build construction of $15.2M water reuse project. MidAtlantic.apa.net.

- US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2018). Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL).

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). Municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) permit. Public Works and Environmental Services.

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). Stormwater Service District. Public Works and Environmental Services.

- Washington Post. (2018) Forget Silicaon Valley—The Dulles Tech Corridor is Cultivating Companies that Break the Mold.

- Moloney, C. (2014). Payback period for low flow toilets: Is cost offset by water savings? Poplarnetwork.come (June 26, 2014).

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). Tysons—Comprehensive Plan.

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). Tysons—Environmental Stewardship, Green Buildings.

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). Watershed Education and Outreach. Public Works and Environmental Services.

- Scruggs, G. (2015). How much public space does a city need? NextCity.org.

- US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2018). Learn About Green Streets.

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2017). Franklin Park and Chesterbrook Neighborhood Stormwater Improvement Project (SIP). Department of Public Works and Environmental Services.

- Washington Post. (2018). Immense Rains are Causing More Flash Flooding and Experts Say its Getting Worse.

- Fairfax County, Virginia. (2018). Embark Richmond Highway Plan approved; Brings bus rapid transit, development.