Global sanitation efforts gone to waste

August 23, 2022

By Kate Leftin

Kate Leftin’s blog post, below, was written as an assignment for Elizabeth Hurley’s class on intercultural competency as a part of the Executive MNR program. A key competency for students who aspire to work in the sustainability field is the ability to communicate across cultural differences found at local, regional, national, and international levels.

Hurley elaborates: “One of our goals is to prepare students to span cultural boundaries and develop innovative solutions that are culturally appropriate and effective. This particular assignment was designed to introduce students to a real-world example that illustrates the need to develop intercultural competencies to solve sustainability challenges.”

In the United States, we take toilets for granted, but 40% of the world doesn’t have access to one. Instead, they relieve themselves in fields and streams. It’s a practice called open defecation and it causes bits of feces, along with all the diseases they carry, to land in people’s food and water. As a result, diarrhea has become the second leading cause of childhood deaths globally.

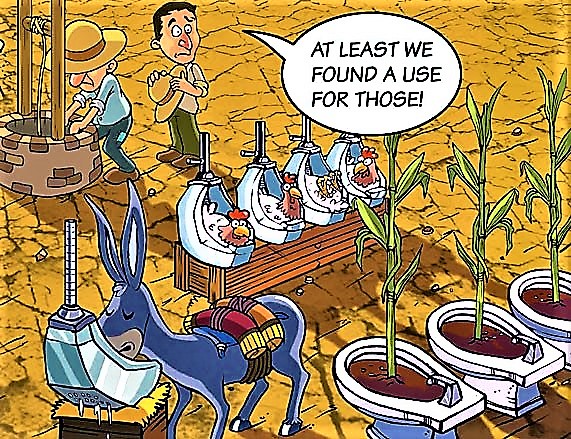

Well-meaning governments and NGOs assume that building latrines will fix the problem, only to find that residents have many other uses for them that don’t include bowel movements. Just adding latrines does not address the values, social norms, rituals, and beliefs that cause people to prefer a field over a toilet for their waste. In other words, latrines don’t always fit into the cultural context of residents that are meant to use them.

Efforts to provide latrines for rural communities of the Odisha state in India provide a good example of how good intentions can go to waste. Residents widely practiced open defecation, even after they received latrines, and had their reasons for doing so. It provided time for socializing. Residents perceived it to be more sanitary to do their business away from the home. Men perceived it to be more convenient to go in the fields where they worked, and women found it inconvenient to fetch water for latrine flushing. Everyone found the latrines unappealing, as they were small and often in disrepair.

Community-led total sanitation

The story of Odisha shows that sanitation projects must involve community members if they are to succeed. Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) arose out of an effort to do just that.

In the 1990s, when rural communities in Bangladesh were hit hard by diseases stemming from open defecation practices, engineers installed toilets with the assumption that residents would use toilets if they had access to them. Like the story in Odisha, that’s not what happened.

When an innovative developer named Kamal Kar talked to villagers in Bangladesh, it revealed that the reasons for using toilets were not at all obvious to them. It seemed more hygienic to leave waste far from the house. He decided to involve the community in the process of mapping where they defecated and where it went, they realized they were eating each other’s poop! Suddenly residents were a lot more motivated to use toilets. Not because they were told to, and not because they were given toilets, but because they wanted to change after seeing that their current practices were less hygienic than they had thought.

This is not to say that CLTS is a prescriptive model that will work everywhere. WaterAid looked at cultural barriers to implementing latrine use in some rural communities of Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Nigeria. These were communities where CLTS had been less successful. While communities differed in the reasons for preferring open defecation, some themes that emerged were:

- Residents felt shame if they were seen going to the toilet.

- Residents wanted to remove feces from the house due to the smell.

- Some had the belief that using a latrine would shorten their lifespan.

- Some had the belief that latrines are meant for the wealthy, and they should not try to imitate them by using one.

CLTS is meant to elicit feelings of disgust about not using latrines, but these cultural beliefs were less about disgust from feces and more about aversion to the latrine itself.

Engaging with culture to motivate and inspire change

It is worth noting that there were also cultural reasons that supported latrine use. When a young woman married into a family, she would go to live with her husband and his family. The male head of the household was very protective of the new daughter-in-law, and latrines were seen as a way to protect her from the threat of theft or assault while defecating in the open at night. Fears of rape and snake bites in some communities also acted in favor of latrine use.

Effective ways to engage the community rely on finding the cultural levers that can best motivate people to adopt desired behaviors. While models like CLTS can provide a guide, it will need to be tailored to fit the cultural context of the residents by involving them from the beginning. Otherwise, residents will use latrines in ways relevant to them while their sanitation practices remain unchanged. If local influencers are engaged from the beginning and can communicate the culturally relevant benefits of latrine use, they may be able to nudge social norms away from open defecation.

Kate Leftin is currently earning her Executive Master of Natural Resources at Virginia Tech’s Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability. She became interested in how environmental problems affect human health during her previous social work career, and strives to create sustainable and resilient communities. She earned her Master of Social Work from Washington University in St. Louis, with a concentration in Social and Economic Development, currently volunteers with Citizens’ Climate Lobby and the Nature Conservancy. She is also a member leader of the Convening Climate Collaborators interest group within American Society for Adaptation Professionals (ASAP).