Global Sustainability and the New Urban Agenda

By: Marshall B. Distel

August 6, 2018

In October 2016, leaders and policymakers from around the world convened at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) in Quito, Ecuador to adopt an initiative known as the New Urban Agenda. More than 36,000 global leaders from 167 countries came together to promote a new model of sustainable urban development to better address social, economic and environmental issues within urban areas (Schindler et al., 2017).

The Habitat III Conference was organized in an effort to support the implementation of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. More specifically, Habitat III was instrumental in moving forward with Sustainable Development Goal 11, which has a stated objective of ensuring that cities are at the heart of the sustainable development movement within the urbanizing world. The framework of the New Urban Agenda integrates numerous aspects of sustainable development to promote the growth of inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable urban areas (Caprotti et al., 2017).

A number of goals and strategies were developed at the Habitat III Conference to focus efforts on the unprecedented challenges of global urbanization. Since climate change has become an urgent challenge that threatens urban areas around the world, the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals emphasize the importance of addressing this urgent issue.

The Habitat III Conference introduced the New Urban Agenda to highlight how cities must be seen as part of the solution to many of the world’s most pressing issues. As the world continues to become more urbanized, it will be imperative to incorporate planning objectives related to social and economic growth into future urban development.

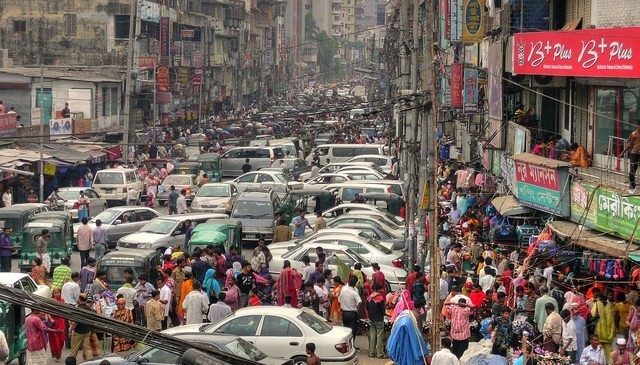

While cities only make up a small fraction of global land cover, they have become one of the main driving forces that have stimulated the global economy. However, as a result of collectively powering the global economy, urban areas are responsible for 75% of global energy use and nearly 80% of human-related carbon emissions (Wu, 2014). The accelerated growth of urbanized areas can be viewed as a double-edged sword since cities not only power global economic growth but also serve as a primary driving force behind climate change (Schindler et al., 2017).

The integration of a wide array of urban-related issues being addressed within a single setting is one of the unique aspects of the New Urban Agenda. The Habitat III Conference was representative of a system’s thinking approach to address the multitude of obstacles that are impeding global sustainability. Because of its wide-ranging impacts to urban areas around the world, climate change was conveyed as one of the contextual pillars of the New Urban Agenda (Schindler et al., 2017).

Cities around the world face extraordinary threats from the impacts of climate change (Araos et al., 2016). Since many of the world’s largest urban areas are located in flood-prone coastal regions, cities have become especially vulnerable to rising sea levels. Moreover, the increasing prevalence of floods, droughts, heatwaves and other natural disasters will continue to threaten many of the world’s most vulnerable populations if action is not taken against climate change.

The International Organization for Migration has highlighted that climate change could become one of the biggest drivers of global migration. It could ultimately force over 143 million people to become climate migrants, most of which are projected to originate from the world’s developing populations in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. (Parker, 2018). Rather than simply casting urbanization as a challenge that is contributing to climate change, the New Urban Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals have highlighted how sustainable urban development can present opportunities for action against climate change within cities (Broto, 2017).

The New Urban Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals explicitly state the need to implement climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies into urban and regional planning. Adaptation and mitigation are two distinct paths that can be employed as strategies to confront the effects of climate change. Mitigation is a strategy that involves reducing the flow of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, while adaptation involves efforts that are aimed at enhancing resilience and limiting vulnerability within a changing climate. The contrast between climate change adaptation and mitigation has spurred numerous debates with regards to the most appropriate action needed to address climate change (Broto, 2017).

Unfortunately, the political divisions that are often associated with adaptation and mitigation have hindered integrated action against climate change. Simultaneous efforts to address both strategies will usually result in meaningful progress against climate change, which is why the New Urban Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals advocate for both.

While it is imperative to address both climate change adaptation and mitigation, it is essential to understand that adaptation is most often framed as a local issue whereas mitigation is framed as a global issue (Broto, 2017). For mitigation strategies to be effective, they would need to be implemented on a global scale. On the other hand, adaptation practices would need to employ city-specific policies to be effective at a local level.

Since the Habitat III Conference is representative of the effort to standardize sustainable urban development on a global scale (Caprotti et al., 2017), it is vital not to forget that all cities are different, and a shared global objective may not yield the same results in all urban areas (Broto, 2017). For example, while the New Urban Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals may advocate for global action against climate change, a shared standardization of efforts may not be as effective as individualized action plans.

Overall, the Habitat III Conference was effective at raising global awareness and a shared vision for action against climate change. However, for meaningful progress to be made to enhance global sustainability, it is necessary for urban areas to develop individualized action plans.

---

Marshall Distel is a graduate student in Virginia Tech’s Master of Natural Resources program. He expects to receive his degree in May 2019.

The Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability thanks the following photographers for sharing their work through the Creative Commons License: United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development; Santiago Ron; b k; and Mathanki Dodavasal.

References

- Araos, M. et al. (2016). “Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Large Cities: A systematic global assessment.” Environmental Science & Policy.

- Broto, V. (2017). “Urban Governance and the Politics of Climate Change.” World Development. Vol. 93, pp. 1–15.

- Caprotti, F. et al. (2017). “The New Urban Agenda: key opportunities and challenges for policy and practice.” Urban Research & Practice.

- Gordon, D., & Johnson, C. (2018). “City-networks, global climate governance, and the road to 1.5C.” Environmental Sustainability.

- Parker, Laura. (2018). “143 Million People may soon Become Climate Migrants.” National Geographic.

- Parnell, S. (2016). “Defining a Global Urban Development Agenda.” World Development. Vol. 78, pp. 529–540.

- Schindler, S. (2017). “The New Urban Agenda in an era of Unprecedented Global Challenges.” IDPR, Vol. 39, pp. 349-374.

- Toly, N. (2017). “The New Urban Agenda and the Limits of Cities.” The Hedgehog Review.

- UCLG. (2015). “The Sustainable Development Goals: What local governments need to know.” United Cities and Local Governments.

- Wu, J. (2014). “Urban ecology and sustainability: The state-of-the-science and future directions.” Vol. 125, pp. 209–221. Landscape and Urban Planning.