If climate change is so urgent, why are we so stuck?: Part 3

June 26, 2024

By Meg Kinney

This article is the third of a 4-part series that is adapted from an independent study by Executive Master of Natural Resources (XMNR) alumna Meg Kinney. The project titled “Finding New Climate Messengers: cultural context for the breakthrough narrative we need” which can be accessed here. (A breakthrough narrative is a forward-looking mindset that invites collaboration and shared possibilities for addressing wicked problems; it is the opposite of a declinist mindset).

This series of articles examines possible reasons why Americans are not mobilizing at scale around what is arguably the most global and complex environmental challenge of our time. Any number of public polls and search queries can easily show that climate change is not suffering an awareness problem so much as it is plagued by a communications problem. Popular culture overwhelmingly paints a pessimistic dystopian future alongside a journalism and media landscape that profits from spreading divisive political rhetoric about what can and should be done about a warming planet. It’s all very overwhelming and you’d be forgiven if you are already feeling weary just reading this post.

The entertainment and information industrial complex is powerful and ubiquitous. We are someone’s target audience every moment we are awake. It is not new news that the power of algorithmic media profoundly shapes cultural and societal sentiment. There are two consequences of this that I believe keep us socially and emotionally stuck:

First, a moral ledger has been created to judge intention.

Political division and our media environment have turned the sustainability conversation into a moral ledger. For every corporation’s good deed, there’s a gotcha meme moment on social media calling out hypocrisy. For every celebrity using their platform to speak on climate, there’s a cultural takedown because they fly private. For every dinner party conversation around shopping green, there’s a “but what about___?” callout for some other environmental sin. This is the very essence of greenhushing – we’d rather say or do nothing than be judged for our attempts to change. Intractable environmental problems are too complex for us to be using this kind of moral ledger that casts our behavior as either 100% good or 100% bad. It’s no wonder we opt out and just let the pundits and the politicians quarrel. Perfection is not the goal, but rather demonstrable, cumulative actions toward the goal. Giving this grace to ourselves and others is in our power, and in our best interest.

Expecting people to do less, use less, or want less while simultaneously questioning their moral compass not only makes people doubt their impact, but it stifles their participation as actors in the system. This is true for businesses as well.

Second, a lack of awe and wonder limits our sense of connectedness.

Awe is a “mysterious and complex emotion” that is said to be self-transcendent; capable of expanding one’s personal boundaries and making us feel an integral part of the universe. Empirical study points to the psychological benefits of the feeling of being small when bearing witness to a beautiful natural scene. A landmark paper in 2003 by psychologists Keltner and Haidt shows that awe-inducing experiences have physiological, psychological, and social effects. Awe can shift mental models; it’s most found in the presence of nature.

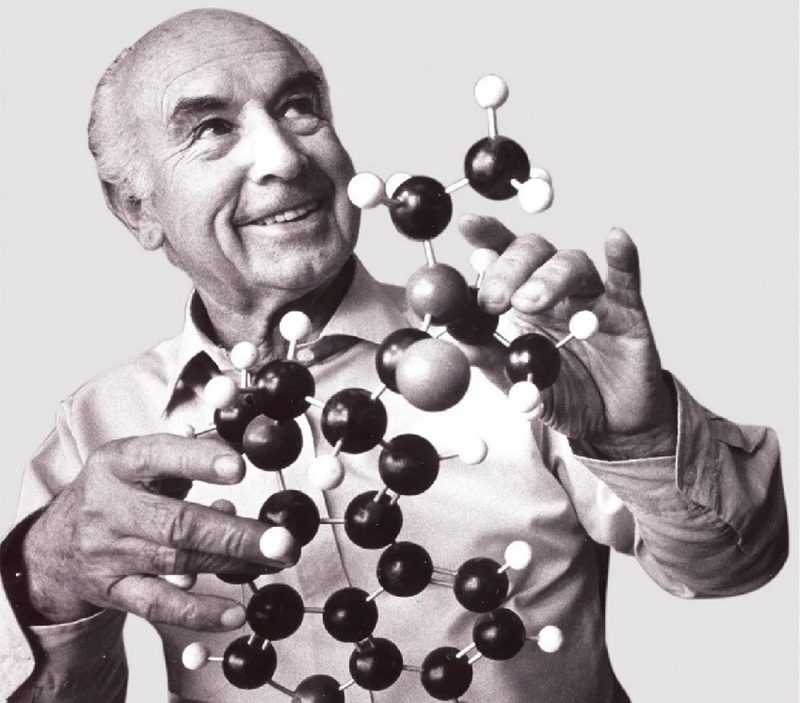

While awe is a distinct concept from consciousness, it is often associated with altered states, attunement to our surroundings, and provoking profound contemplation on connectedness. Consequently, it comes as no surprise that plant-based medicine has a long history in environmentalism, owing to indigenous spiritual traditions and oral histories. Plant medicines might once again be seen as a powerful aid to catalyze the environmental movement, just as they did in the 1970s.

"I share the belief of many of my contemporaries that the spiritual crisis pervading all spheres of Western industrial society can be remedied only by a change in our world view. We shall have to shift from the materialistic, dualistic belief that people and their environment are separate, toward a new consciousness of an all-encompassing reality, which embraces the experiencing ego, a reality in which people feel their oneness with animate nature and all of creation." --Albert Hoffman, 1980

Trivializing this sort of philosophical and psychological discourse as ‘woo-woo’ is a silly fear-based position. Awe and consciousness are profound tools of social transformation – regardless of how they are elicited.

The immediate reward of awe is gratitude, and that’s how we get the ball rolling. In her essay “Returning the Gift”, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer shares wisdom from her Potawatomi ancestors: “Gratitude requires us to pay attention. Paying attention is an ongoing act of reciprocity, the gift that keeps on giving, in which attention generates wonder, which generates more attention – and more joy. Paying attention to the more-than-human world doesn’t only lead to amazement; it leads also to acknowledgement of pain. Open and attentive, we see and feel equally the beauty and the wounds, the old growth and the clear-cut, the mountain and the mine. Paying attention to suffering sharpens our ability to respond. To be responsible…Attention becomes intention, which coalesces itself into action.”

This virtuous cycle isn’t possible if we are weighted by fear, unworthiness, or judgment of our path to connectedness. Being resistant to letting our intention and our attention be hijacked by the 24/7 screen-based content cycle requires a sort of personal vigilance, but our power lies in our own agency to get “unstuck.”

About the Author:

Meg Kinney is an ethnographer and cultural strategist as well as a 2023 graduate from Virginia Tech’s Executive Master of Natural Resources (XMNR) program focused on leadership for global sustainability. She works with brands, sustainability leaders, and social innovators helping them understand the context of progress and telling relevant stories to inspire change.