Investing in a Caffeinated Planet – Part V

By: Nicole Kruz

November 30, 2017

[In the Part I of this series, Virginia Tech Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability alumni Nicole Kruz provided a short Coffee Basics tutorial. Parts II, III, and IV offered an overview of the environmental, social, and economic impacts, respectively, of climate change on coffee cultivation and production. In this, the final installment of the series, Nicole will discuss coffee, climate change, poverty, and sustainability.]

Coffee & Poverty

As noted in the social impacts section of this series, the coffee industry employs over 25 million people around the world, many of whom are smallholder farmers with little capacity to build resilience. In Mexico alone, an estimated 48% of these smallholder farmers still live in poverty (Boot, 2015). Globally, these farmers tend to rely on the coffee crop as their sole source of income, which leaves them vulnerable to shocks to the system, including climate change and market downturns.

There is a proven link between poverty alleviation and conservation in coffee farming communities. When growers are paid fairly, they don’t have an incentive to cut down forests to grow more coffee. ~ Jonathan Colman, 2017

HUFFINGTON POST reporter Kat Fiske (2016) notes that the “struggle of small-scale coffee farmers is not news to anyone in the industry….We are familiar with the statistic that coffee farmers typically earn less than 10 percent per pound of the retail value for their coffee. And we understand that the added costs of agricultural inputs (like fertilizer), cooperative fees and middlemen further cut into what measly profit farmers can pocket from the sale of their beans.”

What can be done to rectify this issue and bring coffee farmers out of poverty?

Factors at Play

In order to address the coffee poverty cycle, it is necessary to first understand the factors contributing to the cycle in the first place. Unfortunately for the farmer, there are many factors to consider. The primary factors are proximity of the farmer to an export market and inability to obtain credit. Due to the preferred growing location of coffee plants, many smallholder farmers live in remote mountainous areas, often with little to no access to urban markets. This forces these farmers to sell to middlemen, who are capable of transporting the crop to buyers for export.

The exchanges often occur at an economic disadvantage to the farmer. The Borgen Project estimates that although coffee beans are produced at $2 per kilo, middlemen can buy the crop for as little as 14 cents (Lamm, 2013). These middlemen will then turn around and peddle the commodity to large corporations, who drastically mark up prices. Known as the ‘Coffee Paradox’, this trading process often results in economic gains for industry but losses for farmers. The result? Many coffee farming families are forced to live in poverty.

Inability to access credit and other forms of lending is also a huge concern for smallholders. The World Bank estimates that “while some traditional lending is available through banks and other financiers, these channels are not always sufficient. In a study highlighted by “Risk and Finance in the Coffee Sector: A Compendium of Case Studies Related to Improving Risk Management and Access to Finance in the Coffee Sector”, it was found that some 60-80% of coffee growers in Brazil – one of the world’s largest producer country’s – use some for of credit to finance production. Inability to access these systems makes it difficult for farmers to maintain their businesses in a lucrative manner.

The contribution of large corporations is noteworthy here. As illustrated in the economic impacts section of this series, multi-national corporations dominate the coffee trade. It is estimated that “farmers tied to these companies cannot recoup production costs. There is no shortage of coffee beans, so plantations compete to offer lower and lower prices to the big companies. … To stay competitive, coffee plantations are notorious for paying subsistence wages and exposing workers to unsafe conditions” (Lamm, 2013).

Without regulatory oversight and corporate sustainability, there are thousands of cases of smallholder famers and migrant coffee workers living in squalid conditions across the world. In Central America especially, up to 40-60 families of migrant workers have been known to reside in one room warehouses with limited privacy and access to sanitation (Zamora, 2013).

These farmhands are also exposed to unsafe working conditions, often being required to apply harmful pesticides to coffee plants without adequate (or any) prior training. Because many farmhands do not have signed contracts, it is easy for their employers to exploit them, making difficult for them to be compensated fairly for their labor. In a recent Fairtrade International and True Price study conducted across Asia and Africa, it was found that only Indonesia provides a sustainable income for coffee growers. Latin America was not featured in the study.

Climate change will increasingly become a contributing factor to the poverty cycle for coffee farmers. Farmers will have to contend with increasing temperatures, more frequent severe weather and disease outbreaks as well as the decrease of land area suitable for coffee growth.

How to Break the Poverty Cycle

To effectively tackle these challenges, “we need to develop long-term, multi-faceted, dynamic, and context-appropriate socio-economic and ecosystem approaches” (Fiske, 2016). One way in which coffee farmers could achieve success would be for them to unionize and demand fair prices for their products.

Non-profits and foundations can also step up to the plate, as is the case with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which in 2008 launched the Coffee Initiative in cooperation with Technoserve. A 4-year grant, the initiative is intended to support 180,000 coffee farmers in Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Ethiopia by investing in new machinery for coffee production that will help farmers improve yield quality and quantity (Baldwin, 2010).

Addressing global trade inequalities and improving the sustainability of the coffee supply chain are by far the best methods for reducing poverty in the industry. The World Fair Trade Organization is striving to do just that, and has developed 10 principles for Fair Trade Organizations to follow to achieve their goal of empowering “family farmers and workers around the world, while enriching the lives of those struggling in poverty” (Fair Trade USA, 2017).

- Improve Opportunities for Disadvantaged Producers

- Increase Transparency and Accountability

- Establish Fair Trade Practices

- Demand Fair Payment

- Eliminate Child and Forced Labor

- Erase Discrimination and Ensure Gender Equity

- Provide Good Working Conditions

- Build Capacity

- Promote Fair Trade

- Respect the Environment

Rather than creating dependency on aid, Fair Trade uses a “market-based approach that empowers farmers to get a fair price for their harvest, helps workers create safe working conditions, provides a decent living wage and guarantees the right to organize. Through direct, equitable trade, farming and working families are able to eat better, keep their kids in school, improve health and housing, and invest in the future” (Fair Trade USA, 2017).

Coffee & Sustainability

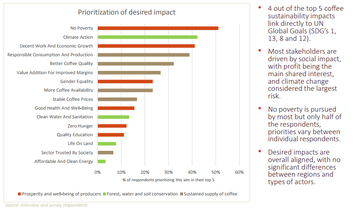

A 2016 study generated by the Global Coffee Platform, the Specialty Coffee Association of America, and the Sustainable Coffee Challenge, which surveyed over 80 respondents, found that large roasters and traders are leading coffee’s sustainability dialogue but that the involvement of growers/producers, particularly smallholder farmers, is too limited. It also found that coffee industry’s sustainability agenda is influenced primarily by consuming cultures. Polled respondents held clear preferences for the sustainability impact they would like to see within the industry. Those located inside the value chain (i.e., roasters and traders) primarily seek to prioritize economic impact whereas those outside of the value chain (i.e., consumers) seek to prioritize social and environmental impacts. At roughly 50 and 45 percent, respectively, zero poverty and climate action rank as the top two impacts respondents would like to see sustainability endeavors achieve.

Activities currently being implemented to achieve a more sustainable industry include, but are not limited to:

- agricultural extension services

- business support

- social inclusion/community welfare

- disaster relief

- diversified farms

- access to inputs: make safe seedlings, tools and fertilizers available

- logistics services

- incentives: provide financial incentives to improve profitability

- traceability and assurance: monitor compliance practices

- value addition: improve processing processes (e.g., washing, roasting)

- demand consumer awareness: conduct outreach education for sustainable coffee

Because coffee production impacts all three pillars of sustainability: environment, economics, and social, it is possible, and arguably imperative, to adopt a systems thinking approach when studying coffee as a crop.

---

[Nicole Kruz is an avid coffee drinker and an alumni of Virginia Tech’s Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability. Ms. Kruz holds an MS in Heritage Conservation from the Technical University of Berlin and a BA in History and German from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Kruz is an environmental consultant for Osage of Virginia, a woman-owned, small business specializing in contaminated site clean-up, federal regulatory compliance, and natural resource management. She currently supports the Office of Environmental Policy and Compliance’s Resource Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Team at the US Department of the Interior. On a daily basis, she leverages skills in project management and inter-agency collaboration to drive strategic planning for incident preparedness and response/recovery activities for oil spills and hazardous material releases. Her focus is primarily on the protection of Natural and Cultural Resource & Historic Properties.]

Literature Cited:

- Baldwin, J. 2010. Brewing an antidote to poverty: Coffee. The Atlantic.

- Boot, W. 2015. Accessed August 8, 2017: https://bootcoffee.com.

- Coleman, JD. 2017. Purchasing coffee mared “shade grown” is good for the planet. Nature Conservancy.

- Fair Trade USA. 2017. Mission and values. Accessed August 10, 2017: https://fairtradeusa.org

- Fiske, K. 2016. Most of the world’s coffee farmers are poor (but we can change that.) Lutheran World Relief.

- Lamm, S. 2013. The Borgen Project: Poverty and the coffee industry. Accessed August 8, 2017: https://borgenproject.org

- Zamora, M. 2013. Farmworkers left behind: The human cost of coffee production. Daily Coffee News.