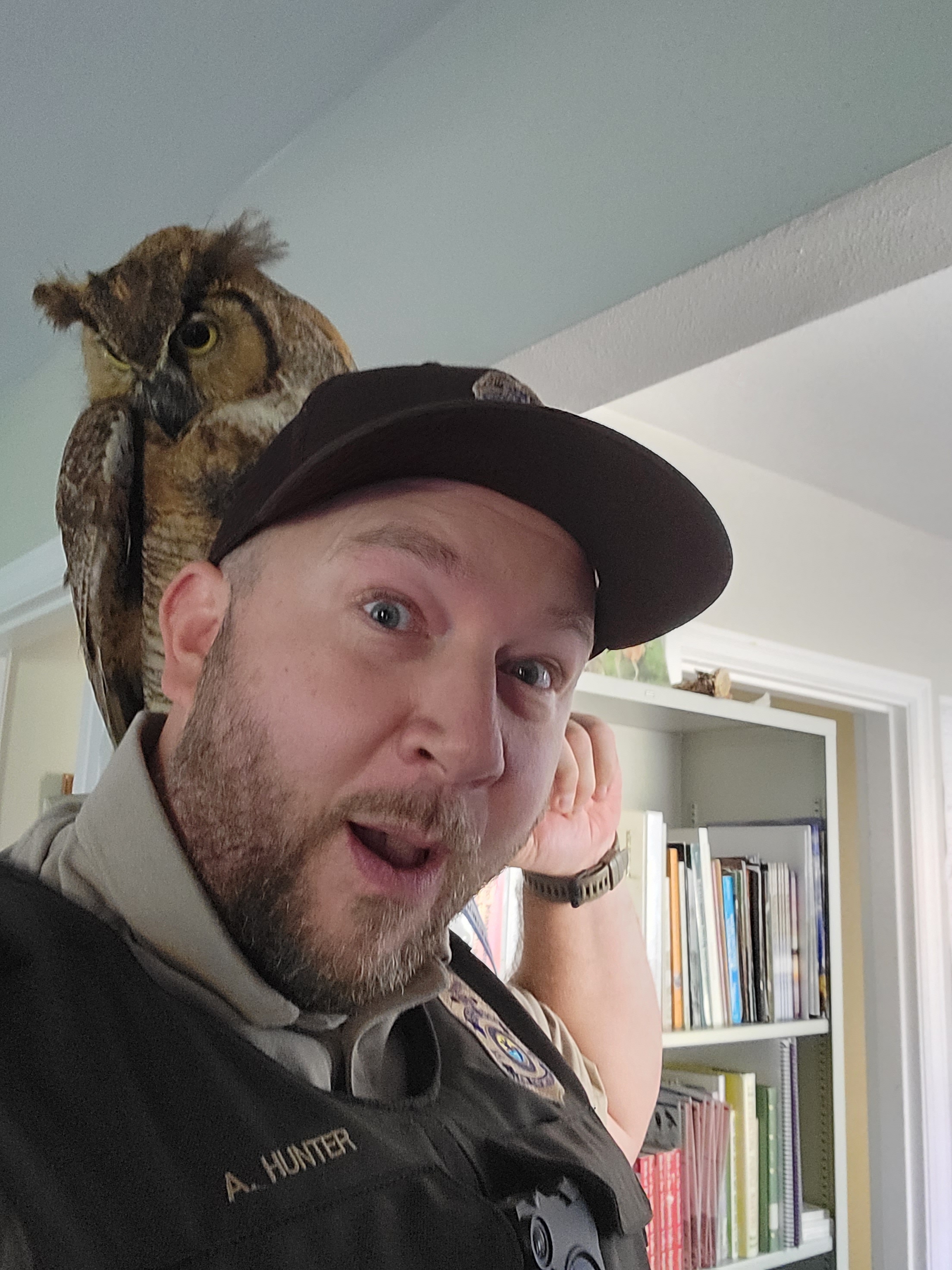

MNR student and Federal Wildlife Officer Adrian Hunter on enforcing wildlife protection with empathy

June 13, 2023

By Lindsay Kuczera

Adrian Hunter was on motorized patrol for the U.S. Forest Service when he was stopped in his tracks: he came across a deer that had been poached in a National Forest. Adrian knew this violated wildlife laws because it was out of season and only a portion of the animal was taken. “I felt with the extensive training I received in the Marine Corps I still had the capacity to make a difference, and felt an urgent call to actively protect wildlife,” Adrian said. He answered that call and was accepted into a training program to become a Federal Wildlife Officer with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

At that time, Adrian was enrolled in Virginia Tech’s Master of Natural Resources (Online) program, but was able to pause his degree while he underwent rigorous training. For a year, he went through federal law enforcement training and federal wildlife officer basic training. “In our work, we focus on enforcement of federal wildlife laws to meet our mission to administer a network of lands and waters for the conservation, management, and, where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife, and plant resources and their habitats,” Adrian said.

This competitive and prestigious program drew 2,200 applicants, with only 18 selected and 16 making it through to be awarded full commission. Now that Adrian is among the few fully commissioned, he patrols an area of roughly 60,000 square miles of fish and wildlife habitat that spans Nevada and California. He is tasked with enforcing federal wildlife laws on National Wildlife Refuges.

On any given day

Adrian has no set day-to-day schedule. As a game warden, following a schedule means criminals can work around you, so it’s important to approach every day with flexibility and to embrace spontaneity. On any given day, Adrian can respond to multiple calls — from checking on an abandoned vehicle, to responding to an injured animal, to visiting a school to teach them about wildlife conservation. On the other hand, he said, you could go out on the refuge one day and not encounter a single person or issue.

Every day has the potential to be drastically different than the day before. Given the vast range that these officers work on, they could be in an urban environment in the morning and on top of a mountain by the end of the day.

Action through active listening

Adrian approaches his position with compassion and active listening, much of which he honed during the MNR program. His education in environmental science and wildlife management has helped him understand the concerns of refuge biologists, managers, and visitors. “Through the MNR, I’ve learned how to engage all the voices involved and use my conflict resolution skills,” Adrian said. He also said he felt better equipped to talk to the public when enforcing a law that they may not see clear reasoning for. “The MNR has helped me to not just approach my job from the law enforcement aspect, but also have strong confidence in the conservation aspect of it,” he added.

A voice for the wildlife

Engaging stakeholders is an important aspect of Adrian’s job, but what voice does the wildlife have? Dr. Megan Draheim’s Human–Wildlife Conflict was one of the most impactful courses for Adrian. “We get to see these issues from the animals’ side, which is really important. It helps make sense of a lot of the laws that we use in conservation, and that helps me better explain to the public the reason we do certain things,” he said.

When asked about managing conflict in a way that benefits wildlife, Dr. Draheim said, “I really want my students to be able to evaluate a situation by looking at it through the eyes of all stakeholders, including ones they might not think are important to have a voice. A lot of what we normally consider human–wildlife conflict is really embedded into a larger conflict between people about wildlife, or even conflict that actually has very little to do with wildlife once you dig into it. Ultimately, conservation is about changing human behavior, so really being able to dive into these complicated human interactions can be very useful to people working on biodiversity protection.”

Adrian referenced a particular part of Dr. Draheim’s textbook that has stayed with him through his journey in wildlife protection. It reads: Conservationists themselves rarely examine how their own values and beliefs shape their worldview, drive their sense of moral superiority, or are perceived implicitly or explicitly by others in conflict settings. Taking this statement to heart, Adrian centers his work with empathy and conservation for every person and creature involved. “I ultimately went into this program because I knew that I could make an immediate and tangible impact in conservation.”

Adrian Hunter retired from the U.S. Marine Corps in 2017 but continues to serve the country by working in natural resource management. He spent four years with the U.S. Forest Service managing programs in recreation and climate change mitigation, and served as the director of an avalanche center. Adrian has recently landed his dream job, working as a Federal Wildlife Officer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. When not on duty, he spends time hiking and camping with his family, and volunteers with the Nevada Department of Wildlife as a wildlife educator and hunter-safety instructor. Adrian plans to pursue a Master of Science in Wildlife Forensics after his graduation from the MNR program in the summer of 2023.

The views, comments, and expressions in this article are personal opinions of Adrian and do not reflect nor are associated with any official stance of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.