Oyster restoration in Lafayette River: a success story

October 11, 2022

By Tom Johnson

Oysters provide a multitude of benefits when it comes to marine and coastal ecosystem health. Adult oysters, for example, can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day, directly consuming nitrogen and algae and aiding in the deposition of suspended solids. Oysters not only enhance water quality, they are a keystone species that plays a major role in the food chain. Clearer and cleaner waters mean more submerged aquatic vegetation can grow; the oyster reefs and vegetation provide a great habitat for small fish and crabs, and this attracts larger species.

In a report for Virginia Tech’s Master of Natural Resources (Online) Marine and Coastal Systems course with Dr. Daniel Marcucci, I examined oyster restoration efforts along the Chesapeake Bay, a vital watershed in Virginia. For decades, it has drawn interest from conservation organizations and local governments to restore the oyster population. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF)—a conservation organization whose mission is to restore the bay’s quality—estimates that previous oyster populations were capable of filtering the entire bay in a week’s time, whereas current populations require a year or so.

Understanding the vital importance that oysters play in marine and coastal ecosystems, CBF is prioritizing the restoration of oysters in Maryland and Virginia. CBF has partnered with a number of stakeholders to create the Chesapeake Oyster Alliance and set a goal of adding 10 billion oysters to the bay by 2025.

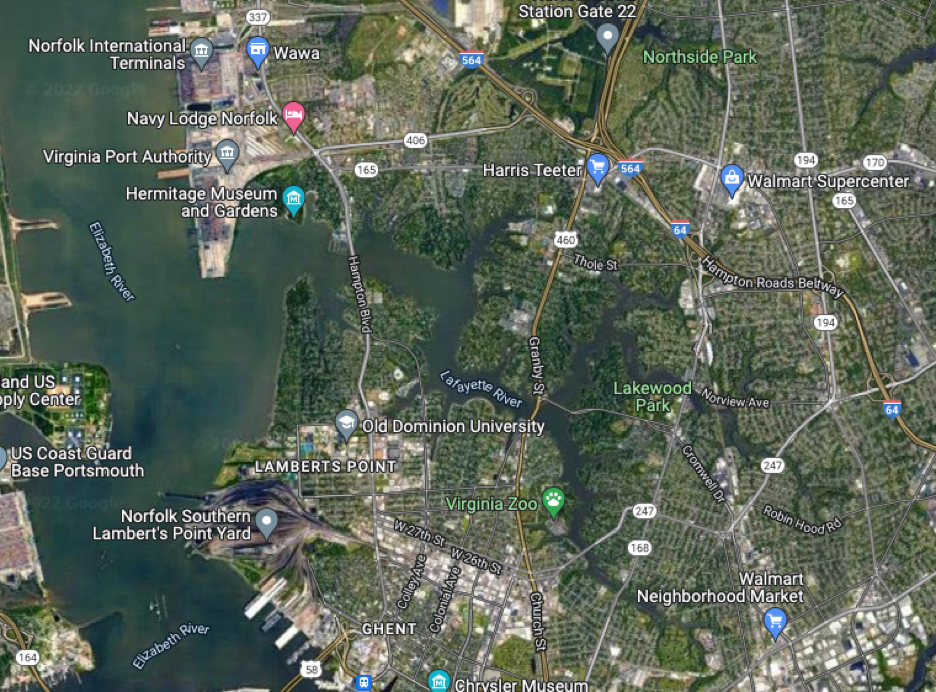

CBF’s work in the Lafayette River is one success story we can learn from and replicate. Lafayette River is a small portion of the Chesapeake estuary surrounded by the urban sprawl of Norfolk, Virginia. The foundation began an oyster restoration project along this river in 2009 and has since placed about 1,500 reef balls (concrete domes with holes that serve as habitat for oysters and other species), planted 470 million spat-on-shells, and created 12 new reefs totaling 32 acres.

The definition of success is not taken from any internal goal, but from standards set by the EPA under the Chesapeake Bay Program. An oyster reef consisting of at least 50 oysters per square meter is considered healthy. By 2021, CBF determined that the reefs in Lafayette River contained between 156 and 365 oysters per square meter.

Restoration projects like this require diverse stakeholder engagement, labor, and funding. For example, CBF worked with a regional nursery to grow oyster larvae that can be adhered to another oyster shell—these are referred to as spat. They also coordinated with local restaurants to recycle and collect oyster shells that are needed for reef and spat development. In another instance, CBF engaged members of the community that have water access to act as oyster gardeners for the first year of reef development, when spat are kept in protected cages under docks and piers in order to become acclimated to the waters. Fostering local relationships like this is an important step in ensuring community awareness and support, especially considering restoration reefs like this are not open to recreational or commercial fishermen. Though the spawn from these healthy reefs can naturally colonize new reefs in other areas that are open to recreational and commercial fishermen.

CBF understands the importance of community outreach while implementing sound restoration methods. The larger interest in a healthy Chesapeake Bay has allowed for sufficient funding from private, corporate, and public sources. Continued monitoring of sites such as Lafayette River allows CBF to quantify success and adapt management strategies as needed. The promotion of such successes leads to further success as it generates financial and public support for oyster restoration throughout the Chesapeake Bay.

Tom Johnson is a graduate student in the Virginia Tech Master of Natural Resources (Online) program. His interests include biodiversity, ecology, and watershed management. Tom is a full-time high school science teacher in Virginia’s public school system where he is able to incorporate his educational experiences with Virginia Tech directly into his classroom.