Transboundary Elephant Conservation

By: Neil Dampier

April 9, 2018

As a photographic safari guide I am fortunate to travel to unique and interesting wilderness locations. In January this year I had the opportunity to guide a safari to Zakouma National Park in Chad.

Established as a national park in 1963, Zakouma is home to an abundance of diverse fauna and flora. However, Zakouma is also a place of great tragedy as well as hope. Between 2002 and 2010, intensive poaching reduced the park’s elephant population by 90%, to only 400 animals. The primary culprits were Janjaweed militants from South Sudan seeking to fund their operations through the illegal trade in ivory.

As a result of stress induced by the poaching, the remaining elephants formed a single mega-herd and ceased breeding. In response to the poaching crisis, Chadian President, Idriss Déby partnered with the non-profit conservation organization African Parks in 2010 to co-manage the park. In the years that followed, African Parks have successfully stemmed the tide of poaching. This protection proved effective such that, over the past five years, Zakouma elephants forego seasonal movement outside the park during the wet season (June-November) and instead remain within the park’s safer boundaries.

As a student in Virginia Tech’s Master of Natural Resources program currently enrolled in the Transboundary Resource Management course, the visit to Zakouma was a perfect opportunity to witness transboundary resource management issues and responses. The boundaries of Zakouma, like so many national parks, were created with limited understanding of ecological processes, animal behavior, and movement. The result is that numerous species that have extensive ranges, including elephants, often have only a part of their home range overlap with a protected area.

Once outside these areas there is often little to no legal or functional protection for these animals who increasingly come into conflict over resources with nearby communities. The movement of elephants and many other wildlife species beyond the boundaries of protected areas is further complicated by national boundaries. Research based on the 2016 African Elephant Status Report reveals that a little over three quarters of savannah elephants are found in populations spread across one or more international boundaries.

Each country feels ownership over its elephant populations, and nations often take differing approaches to protection and management with little to no international coordination of activities. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which regulates the trade in wildlife and endangered species, permits split listing of elephants. This means that some countries’ elephant populations have protection that bans all ivory sales while others have status allowing for some regulated trade. These inconsistencies in policy and practice can result in very different protections for the same elephants as they cross national borders.

In Zakouma, with the elimination of poaching and the corresponding reduction in stress, elephants have resumed breeding. The most recent aerial survey counted 81 new calves. In addition, the mega-herd is slowly starting to separate into the original family groups, and historical seasonal movements outside the park are expected to resume. In response to these changes African Parks are adopting two strategies, to expand the area under protection and to gather data on elephant movement. In October 2017 the area under protection and management of African Parks was expanded to the Greater Zakouma Ecosystem, which includes an additional 11,000 square miles of faunal reserves and wildlife corridors. To put this in perspective, Zakouma National Park covers 1,200 square miles.

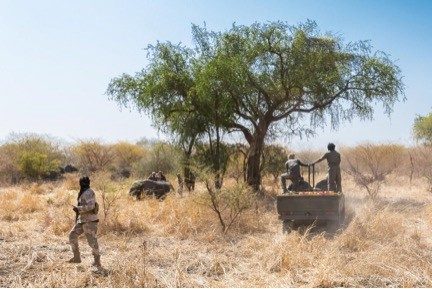

Meanwhile, an additional 29 GPS collars have recently been attached to elephants in the park. The data generated by these collars will allow African Parks to adapt their protection and management strategies as the elephants begin to move beyond the park’s boundaries. I was fortunate enough to accompany the African Parks team on one of these collaring exercises. This involves a spotter plane which locates the herd and guides the ground team towards them. Once within about a half mile of the elephants, two veterinarians along with two assistants move in on foot to dart the chosen elephant. Once the animal succumbs to the sedative, the remainder of the ground crew move in on vehicles to begin fitting the collar. While this is happening, vital signs are monitored and additional data gathered on the elephant before an antidote to the sedative is administered. The whole operation from when the elephant goes down to when it is back up and, on its way, albeit someone confused by what just happened, takes approximately 20 minutes.

The challenges of transboundary management of elephants and the corresponding relationships between conservationists, governments, and local communities need to be overcome to effectively eliminate poaching, protect habitat, and to sustain elephant populations into the future. The wholesale slaughter of elephants in the past decade makes this a more urgent issue than ever. The professionalism and dedication of the African Parks team in Zakouma and others like it offers a glimmer hope for a successful outcome for elephants.

---

Neil Dampier is a graduate student in Virginia Tech’s Online Master of Natural Resources program. Neil is a private safari guide and Associate Executive Director of NorthBay Education, a nonprofit that provides environmental education and leadership training to public school students from across the mid-Atlantic. Neil’s guiding is focused on Africa where he is originally from, and provides authentic explorations of local cultures and wilderness areas. He is an accomplished photographer (www.neildampier.com) and uses is work to highlight the beauty of nature and the need to protect it.