Biopolitical Disaster

September 25, 2017

It was as if God had decided to put to the test every capacity for surprise and was keeping the inhabitants of Macondo in a permanent alteration between excitement and disappointment, doubt and revelation, to such an extreme that no one knew for certain where the limits of reality lay.

~ Gabriel Garcia Marquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

In One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez describes an ill-fated town named Macondo. Ironically, the oil prospect where Deepwater Horizon was sited shared the same name. Marquez’s words seem to have foreshadowed the Deepwater Horizon tragedy. Macondo, for Marquez, and in the case of Deepwater Horizon, reflect the fate of the accursed—impending disaster awaiting those too arrogant to heed warning signs.

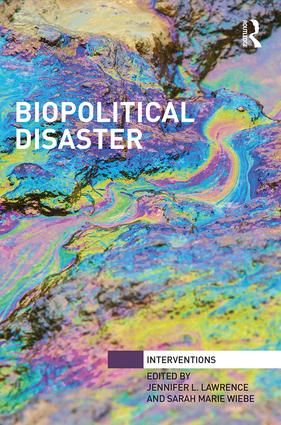

Extreme profit potential was bound up within Deepwater Horizon. But, this was complicated by the extreme risk associated with deepwater drilling. And, while many of the characteristics of Marquez’s Macondo might also be attributed to the Macondo drilling prospect, the devastation that resulted from the explosion aboard the rig on April 17, 2010 was certainly not part of a fictional tale.

Like Deepwater Horizon, the astonishing effects from the many disasters of our time are often more distressing than many of us could have ever imagined.

Economic and social inequality, for example, have long created an untenable living conditions for many in the Caribbean islands. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria are recent reminders that the collision of climate-change and inequality sustain the biopolitical effects of disaster. Impending disasters are not only related to geographic vulnerabilities but are amplified, and prolonged, by the socio-economic vestiges of colonialism—in some cases poor or corrupt governance, humble infrastructure, and widespread poverty mean that warnings cannot be heeded.

Contextualizing such always already precarious life, Biopolitical Disaster addresses a range of cases in which the ruinous effects of uneven power relations materialize. It is not just the unprecedented nature of Deepwater Horizon or Hurricane Irma that characterizes disastrous biopolitics but, also the everyday environmentality that produces vulnerability. My collaborators and I work to expose the productive/destructive force of institutions, discourses, and practices, as well as the cascading effects thereof. Acknowledging the pressures of the Anthropocene, Biopolitical Disaster demonstrates how systems of power and oppression might be understood as intimately interwoven into the very fabric of life.

In the case of Deepwater Horizon, such systems of power were bound up within the constellation of risky terrain and complex technology, colliding with an oil hungry global economy and lax governmental regulations, one of the most gripping environmental disasters in modern history was created. The immediate consequences of the explosion unfolded before our eyes, playing out on televisions, in newspapers, and through online media, raising concerns about preparedness and responsibility for the catastrophe. But, once the well was capped and the daily media attention faded, less-visceral cascading disasters have been revealed. Disintegrated ecosystems and livelihoods as well as a range of public health crises that are still rising to the surface can be counted among the repercussions of the disaster.

What biopolitical disasters clearly reveal is that a global economy run on oil endorses suffering for certain populations, depending on an individual’s ability to resist or respond to the production of violence in a structurally unjust political economy. This suffering is not dissimilar to those enduring the after-effects of hurricanes, flooding, wildfires, droughts, earthquakes, and other environmental crises in our contemporary world.

While those who have enough surplus wealth, knowledge, and necessary means to extract themselves from the immediate geographies of biopolitical disaster might achieve temporary relief from the acute consequences disaster. But, there are a range spatially and temporally dispersed effects under climate change which are as inescapable as the fate of those living in Marquez’s doomed town, Macondo.

As neoliberal governance has dismantled the state’s obligation to intervene on behalf of citizens, communities, and ecosystems, it may be that a new consciousness of is required to expose the interwoven political economy and environmentalities of natural resources.

Biopolitical Disaster works toward this consciousness by demonstrating how deeply conflicted environmental governance is interwoven with disastrous effects on human and non-human life.

Dr. Jennifer L. Lawrence is a member of Virginia Tech’s Master of Natural Resources faculty, and a Post-Doctoral Research Associate at the university’s Global Forum on Urban and Regional Resilience. Her research focuses on issues at the intersection of political economy and the environment, including projects that examine contradictory practices and processes of accumulation by dispossession related to resource extraction and socio-environmental (in)justice. Her book, Biopolitical Disaster, was published in July 2017 by Routledge.

[Thanks to the following photographers for making their images available on Flickr through the Creative Commons License: Florida Sea Grant, Petty Officer 3rd Class Patrick Kelley, and European Commission DG ECHO.]