Expanding the Tribe Through Storytelling (I)

By: Patricia Raun

December 14, 2017

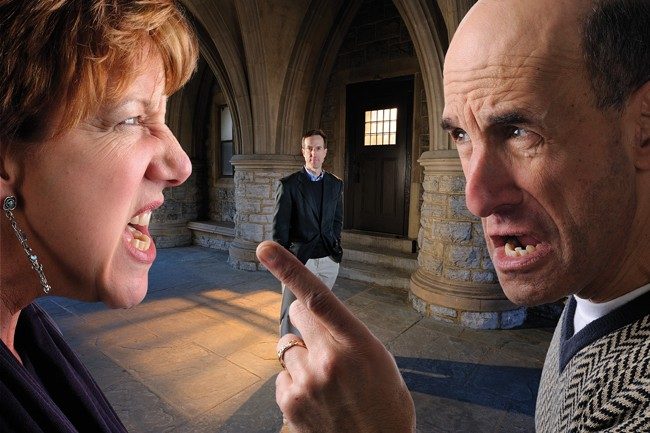

Can you connect across differences? Or do you feel flustered when encountering someone whose perspective is different than yours (on climate change, stem cell research, artificial intelligence, or whatever)? Or worse, just want to give up and retreat to the safety of a like-minded tribe?

Communicating with folks whose values and cultural identity are different from our own is incredibly challenging, sometimes frustrating, and increasingly needed. It requires authentic connection, without which all the information and education in the world is absolutely worthless. It might as well be flushed down the composting toilet to be recycled in the bubble.

Last month, I unexpectedly experienced that elusive and magical bridge of connection and trust. It was on the last leg of a challenging trip — a grueling day of flight delays full of irritable strangers, bad food, and coffee. I was exhausted. For 16-hours I had navigated walkways filled with cyborgs (heads and hearts buried in their cell phones), and immoveable airline bureaucracy. If you’ve traveled much you know about those days.

As I walked to the back of the darkened cabin of the small plane that would hopefully (finally!) get me home I saw that my seat was next to a large African American man of about sixty. He was wearing a ball cap whose insignia suggested that we’d likely be on different sides of many political, spiritual, aesthetic, and intellectual divides. Although I am a believer in community and usually seek an opening for some small exchange of humanity before sinking into my own game of electronic backgammon, I half hoped that he would carry out what has become standard airline behavior: no greeting, no pleasantry, just bury oneself in headphones, iPad, or book and pretend you are alone.

“How are you this evening?,” the man said.

My throbbing brain thought of an appropriate response and my sore throat croaked out, “Tired, but happy to be almost home.”

That was the beginning of my nearly two-hour conversation with a master storyteller – my seatmate wove compelling narratives about painting, literature, his children, the many places he had lived, his hometown of Detroit, his beliefs, his job as a truck driver, and his former career as a teacher. He was fascinating. Though we did have different perspectives on some things, we had important things in common.

As we talked about the stories of our lives I could picture his son and daughter growing up, saw his grandfather training purebred dogs, imagined his mother (a nurse) worrying about him as a teenager. By the end of the trip I felt like we were family. I identified with him. We exchanged contact information. I was inspired, and rejuvenated. I will remember the vivid journey through this man’s experiences as long as I live.

The role of identity in our response to science is central to the work of Dan Kahan, founder of the Cultural Cognition Project and Yale law and psychology professor. Kahan’s work explores gaps between knowledge and belief, and in an article for Advances in Political Psychology, he writes, “There is in fact little disagreement among culturally diverse citizens on what science knows about climate change.”

Kahan goes on:

The source of the public conflict over climate change is not too little rationality but in a sense too much. Ordinary members of the public are too good at extracting from information the significance it has in their everyday lives. What an ordinary person does—as consumer, voter, or participant in public discussions—is too inconsequential to affect either the climate or climate-change policymaking. Accordingly, if her actions in one of those capacities reflects a misunderstanding of the basic facts on global warming, neither she nor anyone she cares about will face any greater risk. But because positions on climate change have become such a readily identifiable indicator of ones’ cultural commitments, adopting a stance toward climate change that deviates from the one that prevails among her closest associates could have devastating consequences, psychic and material. Thus, it is perfectly rational—perfectly in line with using information appropriately to achieve an important personal end—for that individual to attend to information in a manner that more reliably connects her beliefs about climate change to the ones that predominate among her peers than to the best available scientific evidence.

Kahan suggests that “the contamination of education and politics with forms of cultural status competition” is a root of many of our important disagreements – because our belief about scientific topics is deeply connected to our cultural identity – and if the people we identify with (and those we need for protection and community) resist identification with climate change believers, then the result is that we will, too.

Kahan suggests that it doesn’t matter much what we know about things like climate change, but it matters very much how our chosen community identifies itself in the context of those topics.

Stories are valuable tools that work in many ways to build community. They help us expand our cultural identity and understand the identities of others. Images of abstract ideas connected by story bring us together. They bathe our brains in community-building hormones. In identifying with the experiences of my friend on the plane I began the process of expanding my tribe and he expanded his. I am, in a figurative and neurological sense, both myself and my new friend (I will explore this in my subsequent blog post.)

We know in our bones – and research supports – that the shortest distance between two people is a story. As our world becomes ever more complicated and as the divisions among groups grow more and more apparent it is clear that sustainability leaders need to develop several important skills to connect across differences.

As a trained professional actor, I am a fortunate inheritor of an ancient tradition and am a part of a new and growing community of researchers exploring how the tools of storytelling can be applied in the wider world. I am grateful that I can help participants in the Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability at Virginia Tech and those who connect with the Center for Communicating Science skills to build vital connections through stories.

[In Part II of this two-part series, available December 18th, Patricia Raun discusses why storytelling skill is a key capacity for any leader, and especially for those who wish to lead change in the sustainability fields.]

---

Patricia Raun is a professional actor, theatre faculty member, and Director of the Center for Communicating Science at Virginia Tech where she shares the powerful tools of theatre to support skills of connection and communication in scientists, technology professionals, and scholars – helping them to discover ways to become more direct, personal, spontaneous, and responsive. In addition, she is a Fellow at the Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability in Arlington, Virginia where she teaches leadership skills distilled from actor training in theExecutive Master of Natural Resources program. From 2002 – 2016 she served as the founding Director of the School of Performing Arts at Virginia Tech. Raun is an award-winning teacher and administrator. Her applied work in science communication is inspired by her work with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University. Her particular interests include empathy development, serious games and roleplay, collaborative problem solving, and values-based leadership.

References

- Kahan, Dan M., Climate-Science Communication and the Measurement Problem (June 25, 2014). Advances in Pol. Psych., 36, 1-43 (2015). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2459057

- Kahan, Dan M., http://www.culturalcognition.net/blog/2014/4/23/what-you-believe-about-climate-change-doesnt-reflect-what-yo.html

- Zak, Paul J. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

- Zak, Paul J. https://hbr.org/2014/10/why-your-brain-loves-good-storytelling