India Series, Part 1: Real-Time Tragedy in Agrarian Paradise

By: Dr. Bruce Hull

June 4, 2019

Khonoma is a village of 3-4000 people that had thrived for centuries in what looks like an agrarian paradise nestled in the steep and rugged hillsides of Nagaland in northeast India, near Burma. Rich cultural traditions are proudly commemorated, shared, and celebrated. Villagers note that their ancestors successfully resisted Britain’s colonial efforts. The decision circles, pictured above, are where community members gather to speak, resolve conflict, and plan for the future. It is where village elders, years back, devised policies that helped the village maintain its culture and thrive—policies now threatened by global capitalism. Sadly, Khonoma illustrates the real-time dismantling of generations-old knowledge and norms that sustain food, water, culture, and people. This is why I bring Virginia Tech Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability graduate students here—to see, in real time, the negative effects of globalization and to reflect on what can be done to avoid them.

A familiar struggle In Khonoma, generations of learning by doing have produced agricultural practices that sustain natural beauty, cultural integrity, and abundant water, food, and fuel. Several examples:

- Wild vegetables grow abundantly in the village’s commonly shared forests and fields. Residents regularly consume them in daily meals, creating a unique cuisine (worth the trip!). Villagers may harvest as much as their families can eat, but may not sell any excess in the market for a profit. This limit on capitalist trade protects the vegetables from exploitation—people get what they need, but not more to sell and purchase luxuries.

- Families manage their own terraced fields to grow vegetables and rice for their own consumption as well as sale in the nearest villages or city (Kohima). The water on which the crops depend is shared. Clusters of 5-10 terraces are networked so that water flows from one terrace to another. Over generations, the norm emerged that the owner of the lowest terrace controls the flow of water into the top terrace, so everyone is motivated to collaborate and share the water needed for all crops and families to flourish.

- Wild apple trees grow in the village’s commonly owned and managed forest. They produce a delightful and highly sought-after snack of fermented, dried apples. Yum! Demand from neighboring population centers and tourists quickly outpace supply, so dried apple production provides a great way to supplement household income. Why aren’t apple trees over-exploited? A norm has emerged that allows villagers to only harvest apples fallen to the ground; that way, the resource is shared and the trees protected (they break when climbed).

Many other norms and shared practices exist not just to sustain ample agriculture, fuel, and water, but also promote a thriving culture. Crime is low to nonexistent. Elders are respected. Celebrations are common. All the children are well educated. Everyone mourns a death and celebrates a birth. People work hard and have dignity.

Global capitalism is eroding it all. The norms and practices that sustain the commons must be maintained by celebrating the people who conform and shaming and blaming those that don’t. That social fabric is fraying. Wealth leads to inequity that leads to envy. A few families are getting rich by working in the nearest city or, because they are so well educated, joining the professional class elsewhere. Acting in their own rational best interests, those benefiting from capitalism’s rewards build bigger houses, send their children away to better schools, and connect to networks and opportunities outside the village. Factions form within the community that undermines the collective decision-making process.

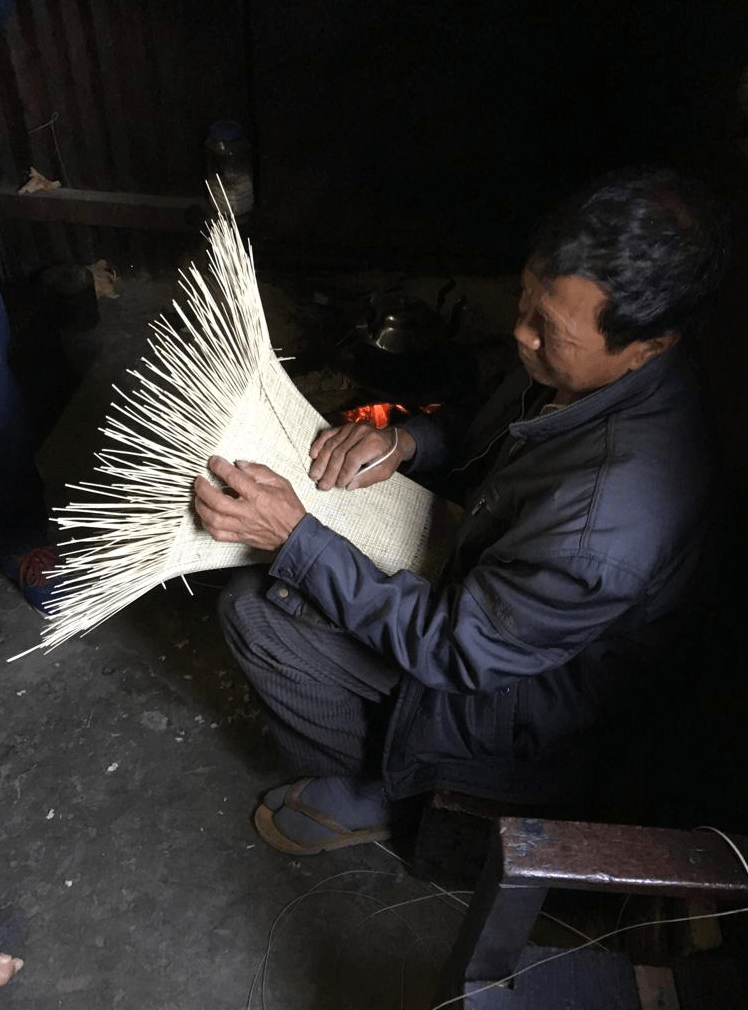

The tourist trap Tourism is first seen as a rational self-interested way for villagers to make money. Residents add rooms and provide homestays. A hotel or two go up. Guided walks emerge, and village homes get visited to view residents as they make baskets, weave tapestries, and cook distinctive cuisine. At first, the village craftsman and craftswomen are flattered by the attention and eager to please. The early explorer tourists, who seek authenticity and happily endure travel hardships, are tremendously respectful. But, looking into the future, it’s easy to see that a different class of tourists will come, wanting escape and entertainment and comfort and service and standards to which they’ve grown accustomed back in the city. The craftspeople will become part of a tour: objectified, demeaned, and turned into roadside attractions.

Khonoma’s traditional culture is a commons resource and villagers don’t have the norms and practices they need to prevent destroying it because village elders, who, over generations of learning by doing, figured out how to sustain tangible resources such as food, fuel, and water, did not create practices and norms for protecting culture from tourism. A few villagers will likely get wealthy before the charm wears off, but Khonoma could lose that special something that defines it. The social fabric could continue to weaken. Further, the transportation systems that the government is improving so as to attract tourists will also enable locals to more easily commute to work outside the village and earn more money than agriculture allows (in part, because global trade keeps driving down the price of commodities). Easily bought food and fuel will replace what villagers now produce with intense and prolonged manual labor. Traditional practices and norms will be forgotten. Another culture will bite the dust. So seems one likely scenario.

The tragedy of the commons Some of the most perplexing sustainability challenges emerge because of this phenomenon: the classic formulation where a few individuals acting in their own best interest put extra cows on the common grazing land, thus increasing their family’s milk productivity and income. Others follow suit. The accumulating pressures of many more cows eventually destroy the pasture, and everyone is worse off as a result. Individually, people are acting rationally; collectively, they act as if insane, creating results no one wants. Capitalism and markets can’t solve many of these problems—but wise village elders could, given the time to do so. Unfortunately, the problems we face today differ dramatically from anything village elders could imagine—climate change and cultural exploitation among them. Fortunately, solutions exist, but they require good governance. Engage!

---

Dr. Hull is a Senior Fellow at Virginia Tech’s Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability in Arlington and a professor at VT’s College of Natural Resources and Environment in Blacksburg. He writes and teaches about leadership for sustainable development and how to have influence in the cross-sector space where government, business, and civil society intersect. He advises organizations, communities, and professionals responding to the Anthropocene. He has authored and edited numerous publications, including two books, Infinite Nature and Restoring Nature. Currently, he serves as president of the Board of Directors of Climate Solutions University and on the advisory council for Virginia Tech’s Global Change Center.