Know Your Climate Bias

By Bruce Hull

Most of us are biased… and that’s a problem. If we can’t overcome our biases, we can’t collaborate well, which means we are less able to coordinate appropriate, effective, and necessary climate action.

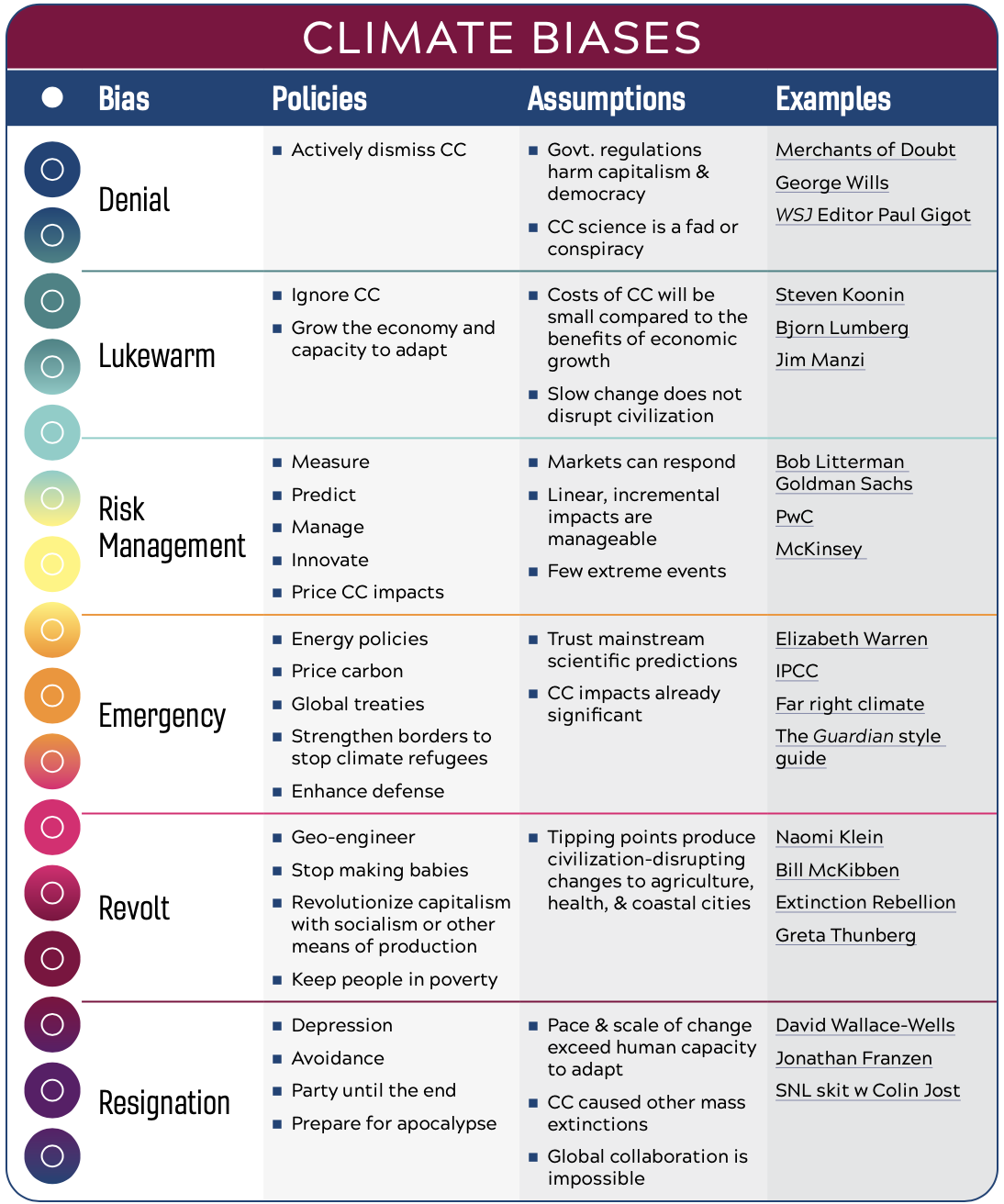

Which biases do you hold? The table below describes six climate biases and illustrates policies, assumptions, and examples of each.

Note that, with the exception of Denialists, the major differences among columns in the table are not due to disagreements about whether the climate is changing or who is causing it. Instead, the disagreements are about what to do about climate change.

The Denialists and Lukewarmers appear similar on the surface but have important differences. Denialists are distinct from all other bias types in that they actively refute, deny, or ignore climate science. They believe that climate action activists want to grow big government, dismantle capitalism, destroy freedom, and other actions that would end American exceptionalism—all outcomes that they find simply unacceptable. Climate science becomes irrelevant—it does not matter if the climate is changing—because the cure is worse than the disease. For Denialists, concerns about protecting capitalism, freedom, and democracy trump all other thinking. The Lukewarmers begrudgingly and cautiously accept that the climate is changing, but believe estimates of impacts to be biased and overstated. They believe climate change consequences will be slow, and can be overcome by prosperity and innovative capacity produced by economic and technological growth; if we promote enough growth and development, then the people of the future will be able to adapt in ways we can’t imagine.

The Emergency and Revolt biases also appear similar on the surface, but also have important differences. Both assume that climate change risks are significant enough to merit giving up some individual control and freedom, so that experts or perhaps a centralized leadership council can coordinate activities. Those holding an Emergency bias believe that experts will be able to reform existing market and governance institutions to meet the emergency. Those holding the Revolt bias, however, believe there exists sufficient risk of catastrophic disruptions to justify untested and perhaps equally risky revolutionary change of major institutions, such as replacing capitalism or subverting developing nations so they don’t emit as much carbon. In a crisis, people are willing to jump out of the frying pan even if it risks jumping into the fire.

Risk Management sits between the Denial and Lukewarm biases on one side and Emergency and Revolt biases on the other. Humanity has overcome challenges of this magnitude in the past, they believe. We have mastered agriculture and food, electrified most homes, overcome most poverty, managed the threat of nuclear war, and are curing communicable disease. People with a Risk bias have confidence in humanity’s ingenuity and believe countries, innovators, and companies will be rewarded with security, profit, brand recognition, and market share as they solve climate-created challenges. That is, climate change is a challenge that technology can solve.

Collaborative leadership practices for managing your biases and navigating the biases of others:

Self-Awareness: You need to know yourself before you can know others. Where do you fall in the table above—what is your bias? How many other biases can you recognize? Self-awareness is difficult and uncomfortable. It requires introspection and feedback most of us would rather avoid.

Buffering: Many of us lack the language, logic, and confidence to share and explain our biases with people who hold different biases. Buffering is a deliberate process of sharing our biases with people holding the same biases—perhaps with people of the same organization, neighborhood, demographic, or profession. Not only does buffering help us become aware of our own bias, it also helps us develop the language, confidence, and comfort to explain it to others.

Recognize Differences: Once you recognize your own biases and are comfortable explaining them, then you need to recognize and accept that other biases exist, and that people use those biases to understand and interpret the world in ways that differ from how you understand and interpret the world. Think of them as different rather than wrong.

Practice Active Listening and Empathy: Listen for the merit in someone’s arguments instead of its weaknesses. Ask questions that draw them out, and create safe spaces for them to explain their positions and values. Suspend judgment and evaluation and instead strive for clarification. To disagree well, you must first understand well.

Interests, not positions: Interest-based negotiation teaches us to avoid leading with positions—such as cap-and-trade—because it locks people in to defending positions they differ on rather than exploring interests they may share. Use the biases comparison table to question assumptions and explore common ground.

Regardless of what you think about climate change, you can’t deny that the topic is of growing importance in local, national, and international discussions. The outcomes of those discussions will be better if you participate and find ways to collaborate. Develop the skills to engage and influence others. It is something that my students in the Executive Master of Natural Resources program at the Virginia Tech Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability learn to recognize and navigate throughout their graduate work, and, I believe, can be an important skill for anyone.

Useful References on Framing Climate Action

- Lakoff (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environmental Communication

- Blyth, Digle, Baird (2019). Meaning of environmental words matters in the age of fake news. The Conservation

- Makower. (2019) What’s the (right) word on climate change? Greenbiz

- Kamaarck, E. (2019) The challenging politics of climate change. Brookings Institution

Dr. Hull is a Senior Fellow at Virginia Tech’s Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability in Arlington and a professor at VT’s College of Natural Resources and Environment in Blacksburg. He writes and teaches about leadership for sustainable development and how to have influence in the cross-sector space where government, business, and civil society intersect. He advises organizations, communities, and professionals responding to the Anthropocene. He has authored and edited numerous publications, including two books, Infinite Nature and Restoring Nature. Currently, he serves as president of the Board of Directors of Climate Solutions University and on the advisory council for Virginia Tech’s Global Change Center.