Learning science your way–inspiring young students in the field through STEAM

March 7, 2023

By Lindsay Kuczera

Modern science can often be too technical, complex, and alienating to reach the general public, and this can deter many students from engaging in science in their youth. What if there were a better way to learn these hard skills so that students felt comfortable entering into STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) regardless of their personal learning styles?

When students are given the space to learn through various methods, science can connect us with ourselves and the world around us. This is Dr. Desiree Di Mauro’s mission for her undergrad and college-level high school Mandala Project, a project which allows students to explore STEM topics using art as well as classic scientific skills (STEAM). Approaching science in unconventional and creative ways is also her goal for her students in Virginia Tech’s Master of Natural Resources program.

Communicating science

The way in which we communicate science can vary depending on your audience, and all approaches are needed in today’s world. In fact, Patty Raun, a faculty member in the Executive MNR, leads this work in Virginia Tech’s Center for Communicating Science, which creates and supports opportunities for people from all sectors and walks of life to develop their abilities to communicate science and connect across differences. Many of the high school and community college students who embark on Desiree’s year-long STEAM project are interested in science and enjoy research, while others are interested in the environment and arts.

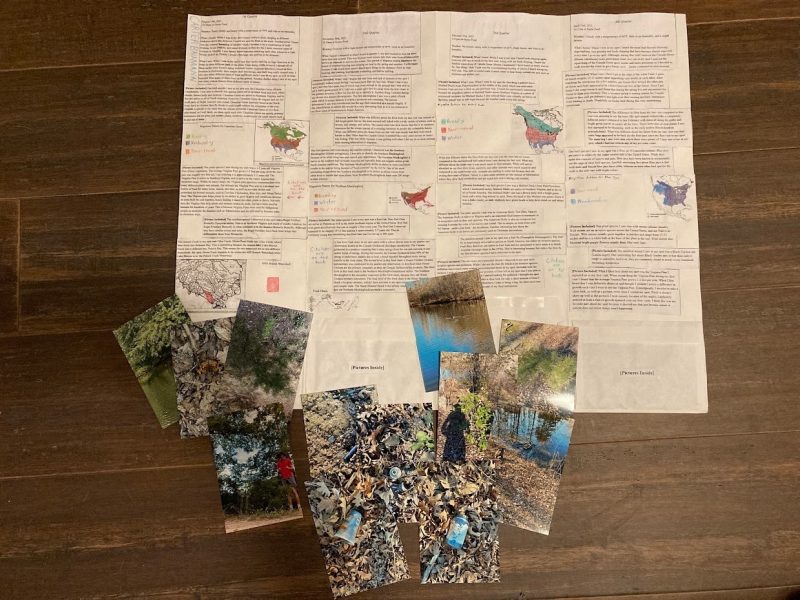

During the course of the Mandala Project, students pick a location that they’re interested in—whether that’s a nearby lake or a specific place in a park. They visit this location four times a year, sit quietly, and observe everything around them for a minimum of 45 minutes. Then they present every quarter based on their most recent outing. These observations are accompanied by research on variables like weather conditions, biotic diversity, and the wildlife they see. Many students go into detail on the native versus non-native species they observed, the climate and weather effects in their area, and how the ecosystem changes over four seasons. Students are expected to ask questions based on their observations and really search for detailed answers to these questions. Desiree grades students on their research, but the way they present their findings is entirely up to them. She has found many students present their findings in a way that resonates most with them, such as a PowerPoint, narrated video, scrapbook, embellished field notebook, or four-issue magazine.

Leaning into your local environment

Desiree stressed that this program is not only a way to have students connect more with nature through science, but also for them to connect with their local environment. In school, we often learn about distant and foreign places, but we cannot name the native birds in our area. “This is really meant to connect students to where they live. It’s a way of getting high school and college students more in tune with their actual environment instead of someone else’s,” Desiree added.

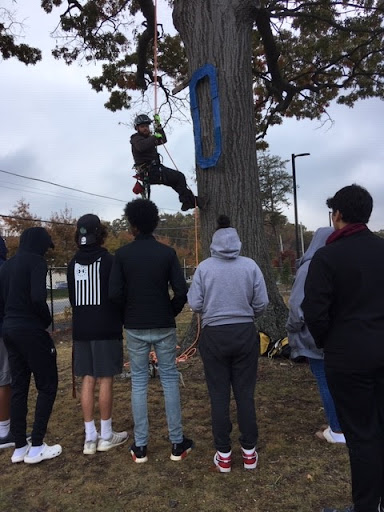

The program also exposes students to fieldwork, which is great for building confidence and problem-solving in budding scientists and conservationists. They learn how to use certain tools for field work, including hard copy and electronic field guides.

Desiree brings similar teaching techniques from the Mandala Project into the MNR courses she teaches, which include Water Conflict and Management, Conservation Biology, and Biodiversity Policy. The MNR includes an international sustainability lens, but Desiree always makes sure to tie those global case studies back to the students’ locality. "I think it's super important for people to understand the ecosystems where they live because that's where they spend time, it’s where they vote, it’s where they interact with the environment,” said Desiree.

This is largely because of advice that Desiree received in her undergraduate and graduate studies when she was fixated on international issues and problem-solving. She learned that you first need to become an expert in a subject—such as water resources or endangered species—and then you can take those skills overseas. “Don’t try to be an international expert if you don't have expertise in something specific. I found that to be one of the most helpful pieces of career guidance I had ever gotten,” she added.

Inspiration for the Mandala Project

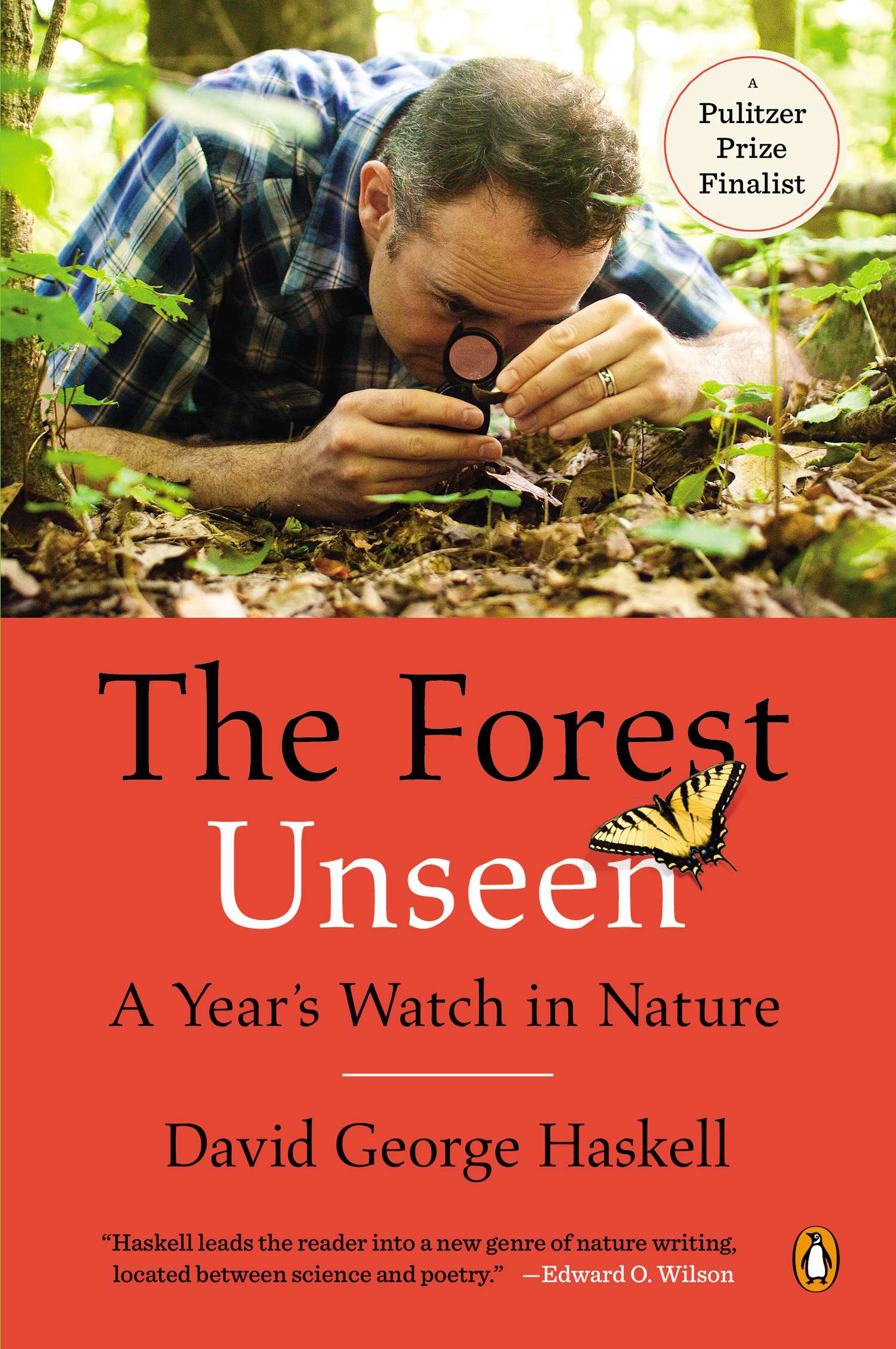

Desiree shared that the inspiration for her program is the book The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature by biologist and author David Haskell. In this book, Haskell visits a one-square-meter patch of old-growth Tennessee forest almost daily for one year and documents his findings of nature's path through the seasons. In vivid detail, Haskell writes how we can merge humanity and science to deepen our understanding of the Earth.

“Wild animals enjoying one another and taking pleasure in their world is so immediate and so real, yet this reality is utterly absent from textbooks and academic papers about animals and ecology. There is a truth revealed here, absurd in its simplicity. This insight is not that science is wrong or bad. On the contrary: science, done well, deepens our intimacy with the world. But there is a danger in an exclusively scientific way of thinking. The forest is turned into a diagram; animals become mere mechanisms; nature's workings become clever graphs. Today's conviviality of squirrels seems a refutation of such narrowness. Nature is not a machine. These animals feel. They are alive; they are our cousins, with the shared experience kinship implies.” ― David George Haskell, The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature