The Coastal Resilience of NYC (II)

By: Kyle Haynes

May 28, 2018

[In Part I of this four-part series, Virginia Tech’s Executive Master of Natural Resources (XMNR) alumni, environmental consultant, and sustainability professional Kyle Haynes began a conversation on the need for and reasons behind efforts to improve New York City’s coastal resilience. In this installment, Haynes reviews the impacts of recent hurricanes in NYC, and explores what is required to build a stronger, more resilient city]

Hurricane Sandy’s Impacts and the Need for Coastal Resilience

New York City is home to more than 520 miles of coastline with more than 8 million residents, and approximately 400,000 of them live in buildings that are physically vulnerable to coastal flooding and sea level rise. According to 100 Resilient Cities, “Faced with aging buildings, an expanding 100-year floodplain, and rising costs of insurance, New York City’s coastal communities need to be better prepared.”

The East Coast of the United States is a global hotspot for sea level rise, with predicted rates in some areas more than two times higher than the global average. New York City has one of the most heavily developed coastlines in the world, and a tremendous amount of property value and infrastructure within close proximity to the shore. The low elevation coastal environment makes the region particularly vulnerable to the impacts of sea level rise. Moreover, “these vulnerabilities will only be exacerbated in the face of what are expected to be more frequent and more powerful coastal storms, as recent experiences with Superstorm Sandy and Tropical Storm Irene have shown.”

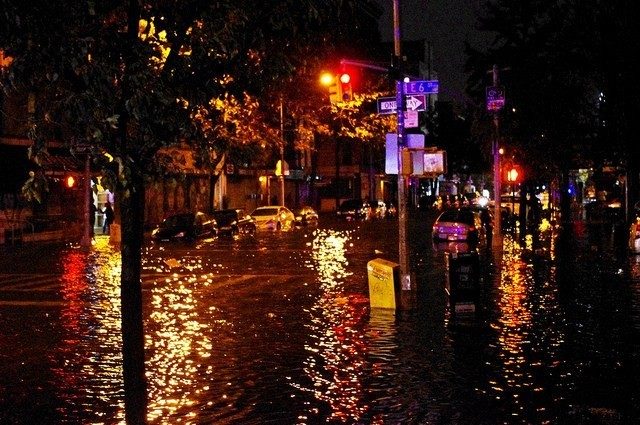

By all accounts, Hurricane Sandy was a dramatic and devastating event for New York City. First and foremost, the tragic deaths of 44 people, displacement of thousands of residents, and the destruction of 800 homes and business and severe damage to 80,000 more that disrupted people’s lives forever should be emphasized. Beyond that, the storm disrupted one of the largest regional economies in the world. It also highlighted and exposed the vulnerability of the social, ecological, and economic systems of the city that are all interconnected including the human impact (loss of life, hospitals shut down, and lack of flood insurance), coastal infrastructure, buildings, utilities, telecommunications, transportation, and water and wastewater. Most of these impacts were a result of storm surge and flooding not necessarily from the wind.

The lack of resilience appears to be fundamentally related to how the city deals with water infiltration. The city infrastructure was not built to handle large amounts of stormwater and flooding. The flooding that occurred during the storm created problems because it impacted other city systems such as their energy supply, economic productivity, food security, sanitation and drinking water, and transportation.

According to Timon Mcphearson, who is the Director of the Urban Ecology Lab at the New School in New York City, “to solve flooding problems in highly interconnected social-ecological systems requires not only thinking about hydrology, but also about the relation of flood-prone areas of the city to transportation networks, population density, building height, electric cable routes, and food distribution.”

A problem as complex as how New York City responds to a hurricane exposes vulnerabilities of the city and highlights that no problem exists in isolation, all are part of a more extensive system of interacting networks; social, ecological, and economic networks. As New York attempts to increase its resiliency from weather-related events, it must be acknowledged that even the most prepared city will not be shielded from hurricanes and other climate change impacts such as sea level rise, storm surges, flooding, and increased storm intensity. However, a resilient coastal city is one that is “first, protected by effective defenses and adapted to mitigate most climate impacts; and second, able to bounce back more quickly when those defenses are breached from time to time.”

A Stronger, More Resilient New York

Back in 2007, Mayor Bloomberg launched a forward-thinking planning document called PlaNYC. It had an ambitious agenda to combat climate change and sea level rise but also improve the quality of life for all New Yorkers. Not many other city governments were thinking about their role in global climate change at that time Mayor Bloomberg knew that because of New York City’s prominence in the world, “it was positioned to take a leadership role on these pressing matters.” Another] report titled A Greener, Greater New York laid out the specifics of the plan and how to achieve the goals within it. After Hurricane Sandy, Mayor Bloomberg “convened the Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency (SIRR) and charged it with analyzing the impacts of the storm on the city’s buildings, infrastructure, and people; assessing the risks the city faces from climate change; and outlining ambitious, comprehensive, but achievable strategies for increasing resiliency citywide. The result is the latest version of PlaNYC – A Stronger, More Resilient New York, completed in 2013.

So how does New City embrace its coastal “vibrant waterfront neighborhoods, critical infrastructure, and natural and cultural resources”? According to a statement in the A Stronger, More Resilient New York planning document, the city “can fight for and rebuild what was lost, fortify the shoreline, and develop waterfront areas for the benefit of all New Yorkers. The city cannot, and will not, retreat.” The impact of Hurricane Sandy’s impact highlights the importance of a systems-oriented approach to building coastal resilience. Dr. Mcphearson summarizes the scenario well, stating that:

“Just as Sandy was not an isolated incident, but part of a larger regional and global climate system that produces weather, including very rare hurricane events, the effects of Sandy on the city were also not isolated, but driven by the interwoven social, ecological, and economic infrastructure of the city. The variation in each system component across the city allowed some areas to be more resilient to the storm than others. Most of the hardest hit areas were low lying and directly affected by storm surges which produced major flooding, but the larger scale effects were not only driven by flooding, but a combination of infrastructure, timing, social networks or lack thereof, energy supply, and, as is the nature of complex city systems, many, many other components.”

In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, New York City aspired to emerge from Hurricane Sandy a stronger and more resilient city. They wanted to be a city that did not just prepare for the next storm but also invested against a broader range of climate threats guided by the New York City Panel on Climate Change and the best available science. “Based on this science, the City developed a comprehensive resiliency plan to rebuild neighborhoods hardest hit by Sandy and to prepare our citywide infrastructure for the future.”

There are hundreds of new projects proposed and funded in the City’s $20 billion OneNYC resiliency program, with investments in physical, social, and economic measures being implemented across the five boroughs to strengthen communities, adapt buildings, protect infrastructure, and improve our coastal defenses. To ensure there was proper leadership in-place to coordinate and implement these projects, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in March 2014, the establishment of the Office of Recovery and Resiliency (ORR). This Office was tasked with leading the City’s efforts to build a stronger, more resilient New York by implementing recommendations laid out in A Stronger, More Resilient New York and in 2015’s One New York: The Plan for a Strong and Just City. The ORR will guide the City’s work to strengthen coastal defenses, upgrade buildings, protect infrastructure and critical services, and make homes, businesses, and neighborhoods are safer and more vibrant. Within this plan, there are strategies for coastal protection that will be critical for building coastal resiliency. The following section describes those strategies.

[In Part III of this four-part series, scheduled for publication on June 4th, Haynes explains four coastal protection strategies developed in response to recent hurricanes and their impact on NYC.]

---

Virginia Tech’s Executive Master of Natural Resources (XMNR) alumni (2017) Kyle Haynes is an environmental consultant and sustainability professional with over 8 years of experience in natural resource management. As a consultant, he leads environmental studies for transportation and infrastructure projects throughout the mid-Atlantic. Additionally, he is a certified Envision Sustainability Professional and Virginia DEQ Combined Administrator in Stormwater Management and Erosion and Sediment Control. Kyle also has a BS in Geography from Radford University.

The Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability thanks the following photographers for sharing their work through the Creative Commons License: David Shakebone; and Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

References

- A Stronger, More Resilient New York. 2013. NYC Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency. <http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/sirr/SIRR_singles_Lo_res.pdf> accessed December 2016.

- Coastal Resilience. 2016. <http://coastalresilience.org/about/> accessed December 2016.

- New York’s Resilience Challenge. 2016. <http://www.100resilientcities.org> accessed December 2016.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2016. What is Resilience? <http://www.oceanservice.noaa.gov> accessed December 2016.

- OneNYC. 2016. <http://www1.nyc.gov/site/lmcr/background/background.page> accessed December 2016.

- McPhearson, T. 2016. Wicked problems, social-ecological systems, and the utility of systems thinking. The Nature of Cities. <https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2013/01/20/wickedproblems> accessed December 2016.

- Rebuild By Design. 2016. <http://www.rebuildbydesign.org/our-work/all-proposals/winning-projects/big-u> accessed December 2016.