The Coastal Resilience of NYC (IV)

By: Kyle Haynes

June 11, 2018

[In Part I of this four-part series, Virginia Tech’s Executive Master of Natural Resources (XMNR) alumni, environmental consultant, and sustainability professional Kyle Haynes began a conversation on the need for and reasons behind efforts to improve New York City’s coastal resilience. Part II reviewed the impacts of recent hurricanes on NYC, and Part III presented four strategies developed to address the coastal resilience needs of NYC. In this final installment, Haynes discusses lessons learned.]

Example Project – The BIG U

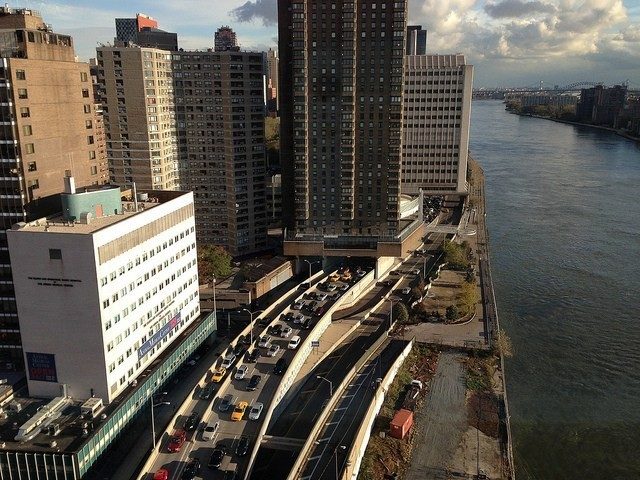

According to Rebuild by Design, “the low-lying topography of Lower Manhattan from West 57th St down to The Battery, and up to East 42nd St is home to approximately 220,000 residents and is the core of a $500 billion business sector that influences the world’s economy. Hurricane Sandy devastated not only the Financial District, but 95,000 low-income, elderly, and disabled city residents. Infrastructure within the 10- mile perimeter was damaged or destroyed, transportation and communication were cut off, and thousands sat without power or running water.”

This project, proposed by Rebuild by Design in collaboration with New York City to protect Lower Manhattan, suggests “10 continuous miles of protection tailored to respond to individual neighborhood typology as well as community-desired amenities. The proposal breaks the area into compartments: East River Park; Two Bridges and Chinatown; and Brooklyn Bridge to The Battery. Each project will provide “a flood-protection zone, providing separate opportunities for integrated social and community planning processes for each.”

In addition, “each compartment comprises a physically separate flood-protection zone, isolated from flooding in the other zones, but each equally a field for integrated social and community planning. The compartments work in concert to protect and enhance the city, but each compartment’s proposal is designed to stand on its own.”

Joining the 100 Resilient Cities

It takes a lot of resources to build a resilient city. The Rockefeller Foundation realized that cities need help and, as a result, the foundation pioneered the 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) network. 100RC is “dedicated to helping cities around the world become more resilient to the physical, social, and economic challenges that are a growing part of the 21st century. New York City was one of the first cities to join the network and as a member is provided resources necessary to develop a roadmap to resilience along four pathways including; funding and logistical guidance for a new city government position, a Chief Resilience Officer; expert support to develop a resiliency strategy; access to solution and partners; and membership to global network of other cities trying to build resiliency.

Along with access to resources, partners, and funding, one of the most critical benefits of joining the 100RC network is the funding and establishment of the Chief Resilience Officer (CRO) city government position. This role works across multiple departments and is responsible for the implementation of the resiliency and sustainability planning, implementation, and strategy development. Without the establishment of this leadership role, it would be difficult to work across so many different departments.

Lessons Learned

As you take a deeper look into what it means for a city to increase their resiliency from many different types of shocks to their social, economic, and ecological systems, you quickly realize how interconnected the systems are to one another. Upon my initial research of coastal resilience, I found that isolating best management practices for coastal protection was only the tip of the iceberg. In reality, many cities, including New York City, had very little investment in resiliency, especially coastal resilience. Therefore, when a natural disaster strikes a coastal city, all of their vulnerabilities are dramatically exposed and the systems that don’t have the ability to adapt are the ones that suffer the most. Recent focus on sea level rise and climate change adaptation throughout the world in major cities has brought resiliency planning into the mainstream, but there is still a serious lack of funding and implementation of holistic coastal resilience projects that truly look at all city system interconnectedness.

I, too, started this project thinking I would be describing more coastal protection practices, but I found out very quickly that that is not where the true challenge is regarding coastal resilience. The true challenge is for cities to overcome economic barriers in implementing resiliency projects that truly protect the city, enhance the economy, and benefit the environment. In order to do that, a city has to have resources, foresight, strategies, planning, policies, and great urban design/engineering. To balance those things takes great leadership. Leadership at the neighborhood, community, and city government scale and even for New York, they need resources from the international community as well via the 100 Resilient Cities network. So the rest of the world is looking at New York City to see what they do, and I will be watching them too.

I found that I needed to decrease the scope of my original research idea of comparing five cities, down to three cities, to ultimately one. The reason for that is that there is so much to learn about how cities make decisions, how they respond to disaster, how they invest in the future, and where planning, implementation, and strategies actually start to get traction (and funding). The more I started to research multiple cities, the more I lost track of what I wanted to discover. As a subject matter expertise paper, I found it much more worthwhile to read through all of New York Cities planning documents as the developed and I was unable to spend adequate time doing the same for other cities.

Since New York City is such a large city, it has a tremendous amount of resources and a lot at stake. Therefore, I viewed New York City as the city that has the opportunity and the most leadership potential to showcase successful pilot projects, long-term coastal resilience strategies, and sustainability that can be used as a model for other cities.

---

Virginia Tech’s Executive Master of Natural Resources (XMNR) alumni (2017) Kyle Haynes is an environmental consultant and sustainability professional with over 8 years of experience in natural resource management. As a consultant, he leads environmental studies for transportation and infrastructure projects throughout the mid-Atlantic. Additionally, he is a certified Envision Sustainability Professional and Virginia DEQ Combined Administrator in Stormwater Management and Erosion and Sediment Control. Kyle also has a BS in Geography from Radford University.

The Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability thanks the following photographers for sharing their work through the Creative Commons License: MTA; MTA; and Mark Lyon.

References

- A Stronger, More Resilient New York. 2013. NYC Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency. <http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/sirr/SIRR_singles_Lo_res.pdf> accessed December 2016.

- Coastal Resilience. 2016. <http://coastalresilience.org/about/> accessed December 2016.

- New York’s Resilience Challenge. 2016. <http://www.100resilientcities.org> accessed December 2016.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2016. What is Resilience? <http://www.oceanservice.noaa.gov> accessed December 2016.

- OneNYC. 2016. <http://www1.nyc.gov/site/lmcr/background/background.page> accessed December 2016.

- McPhearson, T. 2016. Wicked problems, social-ecological systems, and the utility of systems thinking. The Nature of Cities. <https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2013/01/20/wickedproblems> accessed December 2016.

- Rebuild By Design. 2016. <http://www.rebuildbydesign.org/our-work/all-proposals/winning-projects/big-u> accessed December 2016.