The Slow Violence of Sprawl — Part II

September 21, 2017

[In Part I of this series, Virginia Tech Master of Natural Resources student Marshall Distel introduced us to the concept of slow violence, and explained why the term applies to urban sprawl.]

Sprawl and Mass Motorization

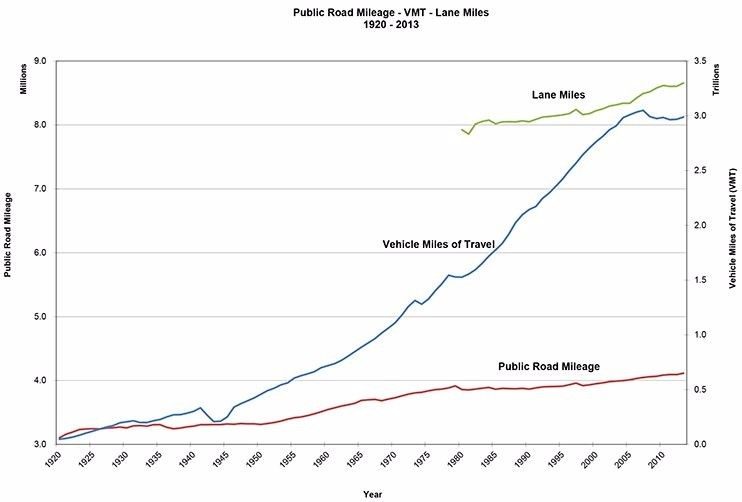

As American communities have continued to spread across the landscape, commuting distances have increased significantly. Sprawl and low-density developments have facilitated an increase in car dependency, traffic congestion, and commute-to-work times (Lucy & Phillips, 2006). In fact, traffic growth and annual vehicle miles traveled have been increasing at alarming rates. The rapid expansion of car-dependent built environments and multiple waves of economic growth have made the United States the most motorized nation in the world (Jones, 2008).

Sprawling developments have traditionally separated residential neighborhoods from workplaces, recreation areas, and shopping establishments. This has made it increasingly difficult for suburbanites to get around by public transit or on foot. The impacts of prescriptive zoning in American suburbs guarantees increased automobile dependency (Benfield et al, 1999). The U.S. has constructed more expressways and highways than any other country in the world in order to support sprawling and car-dependent landscapes (Jones, 2008). Moreover, as more roads and expressways are created, it allows the suburbs to expand outward into more distant regions, which consequently creates a positive feedback loop that requires even more roads to be developed (Jackson, 1985).

Air Pollution and Climate Change

Since sprawl fuels mass motorization and hinders active modes of transportation, it has led to a significant increase in carbon emissions and air pollution. While the automobile itself offers interdependence, and provides high levels of personal mobility, mass motorization is a leading source of air pollution (Kennedy, 1989). As vehicle miles traveled increase, greater quantities of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons, and other particulate matter are released into the atmosphere (Frumkin, 2002).

However, thanks in part to government-mandated improvements, today’s cars produce 80 to 90 percent fewer hydrocarbons and 70 percent less nitrogen oxide than 1960s models (Squires, 2002). Although, even with cleaner burning engines, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency predicts total vehicular emissions could continue to rise as a result of increased driving (Squires, 2002).

While air quality has improved within the United States over the past three decades, greenhouse gas emissions have continued to increase. Sprawl-related automobile traffic accounts for around 26 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions (Frumkin, 2002). Moreover, the transportation sector accounts for nearly two-thirds of American oil consumption (Benfield et al, 1999).

The primary driver of climate change is carbon dioxide, which is generated when fossil fuels are burned for transportation and other uses (Squires, 2002). The sprawl-related increase in greenhouse gas emissions is a prime example of a slow-acting violence. A rise in greenhouse gas emissions poses as a formidable, yet highly overlooked threat to life on this planet. While some of the effects of climate change are visible today, the most disastrous repercussions will likely be postponed for decades into the future.

Water Quality

Sprawling development patterns threaten both the quantity and quality of water (Frumkin, 2002). As green landscapes are cleared to make way for low-density subdivisions and vast swaths of impervious surfaces, less rainfall is able to be absorbed into groundwater systems. When less water is able to be absorbed by groundwater systems, communities that rely on groundwater for their main source of drinking water may be at risk of water shortages. Instead of slowly permeating into the ground, rainfall moves over impervious surfaces, collects non-point sources of pollution and transports them to surface waters such as lakes, streams and rivers (Benfield et al, 1999).

Non-point sources of pollution can come from a wide variety of contaminants like oil, grease, phosphorus and sediment. While point sources of pollution often come from a single source, non-point pollution is excreted from many sources. Sprawl-related water pollution is another pertinent form of slow violence since the visible impacts often go unnoticed until pollutants accumulate to form toxic algae blooms. On the other hand, while the buildup of runoff pollutants can be a gradual process, one of the more visible and catastrophic water-related impacts of sprawl can come in the form of flood events.

Unlike sprawl development, studies have shown that high-density developments can reduce peak flow rates and the overall volume of pollutant runoff (Frumkin, 2002). In hydrology, peak flow is the maximum rate of water discharge caused by a rainfall event. In communities with large areas of impervious surfaces, higher peak flow rates are seen.

As the amount of impervious or covered surfaces in a community increases, the volume and velocity of runoff also increases, which can lead to erosion and flooding (Benfield et al, 1999). Parking lots, driveways, roadways and rooftops are leading causes of increased runoff in suburban areas. Research has shown that large-lot and low-density subdivisions increase the imperviousness of a landscape by 10 to 50 percent when compared to more densely populated developments. Overall, the consequences of amplified stormwater runoff can be visibly dramatic.

Sense of Place

When thinking about the incremental effects of sprawl, a loss of a sense of place is a lesser known impact. In his books The Geography of Nowhere and Home from Nowhere, suburban critic James Howard Kunstler effectively portrays how sprawl has hindered the sense of place within American landscapes. In The Geography of Nowhere, Kunstler describes how sprawl has initiated a transformation from a nation built around livable and accommodating Main Streets, to a country where everyplace resembles no place in particular (Kunstler, 1993).

The concept of the “geography of nowhere” is characterized by how buildings relate to each other in the landscape, and by how they’re arranged in the places that we call “home.” Commercial real estate developments, along with their supportive six lane highways, collectively shape landscapes that aren’t worth remembering. Furthermore, this neglected environment is also distinguished by its total separation of uses. The separation of office parks, factories, schools, grocery stores and residential homes through zoning limitations, have led to detrimental effects on the way that society functions (Kunstler, 1993).

In Home from Nowhere, Kunstler describes how sprawl and single-use zoning collectively continue to eliminate society’s sense of place. “It soon becomes obvious that the model of human habitat dictated by zoning is a formless, soulless, centerless, demoralizing mess” (Kunstler, 1996, p.112). Overall, he conveys how separating private and public buildings in a low-density landscape can be destructive for both the environment and society as a whole. The slow erosion of community identity through the repetitive construction of indistinguishable subdivisions and strip malls continues to wear away our sense of place.

[In Part III of The Slow Violence of Sprawl, Marshall will explore the socio-economic and public health implications of sprawl — watch for it September 28!]

Literature Cited

- Ben-Joseph, E. (1995). “Changing the Residential Street Scene,” Journal of the American Planning Association, 504-515.

- Frumkin, Howard. (2002). “Urban Sprawl and Public Health.” Emory University. 201-217.

- Jackson, K. (1985). “Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States.” New York, NY: Oxford University Press

- Jones D. (2008). “Mass Motorization & Mass Transit.” Indiana University Press.

- Kennedy, D. (1989). “Air Pollution, the Automobile, and Public Health.” Washington: National Academy Press.

- Kunstler, James Howard., 1993. “The Geography of Nowhere.” New York: Touchstone.

- Kunstler, James Howard., 1996. “Home from Nowhere.” New York: Simon & Schuster, 109-149.

- Lucy, W., Phillips, D. (2006). “Tomorrow’s Cities, Tomorrow’s Suburbs.” Chicago, IL: Planners Press

- Squires, Gregory. (2002). “Urban Sprawl: Causes, Consequences & Policy Responses.” Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press

[Creative Commons License photos from Flickr courtesy of: Thomanication, Pete Jelliffe, and Toban B. Thanks also to FHWA for the Public Road Mileage figure.]